Susan Elias still takes her old bicycle for a spin now and then — a 1985 steel Colnago with a friction shift and cables that still pop up. A technological marvel then; an antique in this day of carbon frames, electronic shifting and disc brakes.

“On a group ride in Orono a few years back, the guys were admiring it and said they even have a special retro bike ride day when the oldsters get out their old bikes,” Elias said recently from her home in Orono.

Competitive cycling is largely in Elias’ past; ice hockey and skiing are her sporting choices these days. But in the 1980s, the Readfield native forged a standout career on wheels that peaked with a fourth-place finish in the women’s version of the Tour de France in 1989.

She was rewarded in late March with her election to the Maine Sports Hall of Fame. The 10 new members will be inducted in ceremonies at Portland’s Merrill Auditorium on Oct. 29.

• • •

Elias was a successful athlete long before she wandered into cycling in 1984. At Maranacook Community High, she won conference and/or state titles in cross country, track and cross country skiing. At the University of Maine, she set school track records in the 800-yard run, 800-meter run, mile and 1,500-meter runs. She is a member of the school’s Hall of Fame.

But during Elias’ senior year at Orono, Steve Ridley, a fellow track and cross country runner at UMaine, introduced cycling to Elias, who admitted she was “burned out with running” and had her sights set on graduate school as she neared her degree in wildlife management.

“It was just like falling in love,” Elias said. “I realized I’ve got to ride a bike. I need to do this. It was like, ‘Eureka!’ So I put my plans to go to graduate school on hold.”

Susan Elias poses on the Katahdin View ski trail, one of the New England Outdoor Center nordic ski trails, on March 28, 2020. Elias is a former bicyclist who was recently elected to the Maine Sports Hall of Fame. Photo provided by Susan Elias

Soon, she was participating in small community races and obtained a license from the U.S. Cycling Federation to complete in more formal races.

In September 1985, she took part in her first USCF-sanctioned race, the Race for the Rock in Plymouth, Massachusetts, where she met Betsy King, another encounter that changed her fortunes. King, a world-class cyclist who had just raced in the Tour de France Féminin — a women’s version of the venerable race established in 1984 — “saw a little bit of talent,” in Elias’ words, struck up a conversation and gave her some instruction.

“She said, ‘I’m going to win this race, and I want you to finish second, and here’s how you’re going to do it,’” Elias said. “She told me what to do and who to follow and when to go, so I got second.”

King could tell right off Elias had potential to go far.

“She’s not only very talented physically, she’s also quite bright, so it helps to have both, and she wasn’t afraid of training very intensely,” King — a winner of more than 300 races by her count from 1978-94 — said recently from her home in Connecticut, where she is a nurse practitioner.

“If they’re a teachable spirit — a lot of people do not have a teachable, coachable spirit, and it just doesn’t seem to gel with them — but you have to have both a physical mind and a teachable mind.”

Soon, Elias was racing with the developmental squad on King’s North Jersey Women’s Bicycle Club. Less than a year later, after a winter training with King in California, she was in the Tour de France Féminin and finished 64th out of 90 racers. While Elias described her rapid rise from weekend warrior to international competitor as “ludicrous,” she credits team director Michael Fraysse with taking racers new to the sport and giving them a path to success.

“He was a big champion of women’s cycling back in the ’80s and just women’s sports in general,” Elias said. “If you’re new to the sport, how are you ever going to get on an elite team if you don’t have a pathway? … But with Mike’s development team, if you just showed a little bit of promise and interest and indicated that you were a team worker, then you could be on this team.”

The veteran King, meanwhile, was more than happy to share her expertise in a sport where many athletes jealously guarded their secrets.

“Betsy King made a special project of coaching me up,” Elias said. “… She taught me everything she knew. She wasn’t always interested in being better than me; she was interested in getting me to win whatever I could. And she taught me how to be a good teammate.”

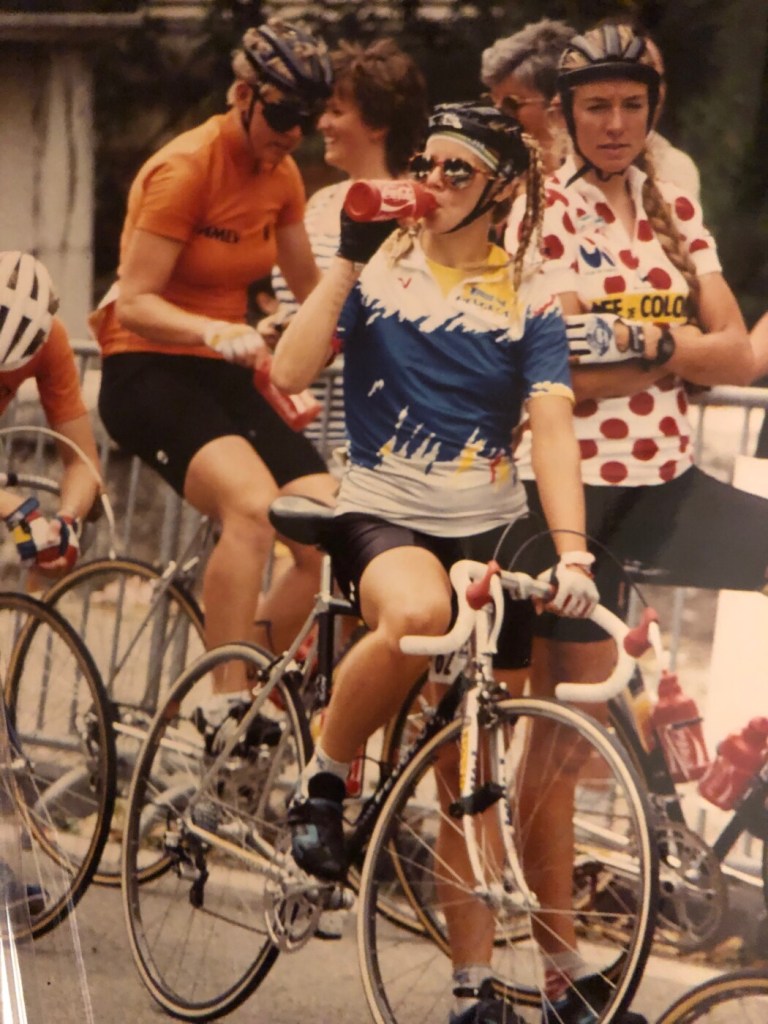

Susan Elias stops for a quick drink of water at the Tour de France Feminin in 1986, not long after she took up the sport. Elias, a Readfield native, is a former bicyclist who was recently elected to the Maine Sports Hall of Fame. Photo provided by Susan Elias

Although individual winners grab all the glory, cycling is a team sport, too. Early on, Elias was a “domestique,” someone to run interference against rivals and help the team’s top cyclist win the race, essentially cycling’s version of a football lineman blocking for a star running back. Her duties also included everything from grabbing food and water for the stars to offering them new wheels in case of a crash.

“(You did) whatever it is you need to do. If you come in dead last, it doesn’t matter if you supported your leader, that’s what it’s all about. It’s a team sport,” Elias said.

King said Elias had an amazing ability to pull away from the pack — “out of sight is out of mind,” she said. At the end of one race in Florida, King and Elias were so far in front they crossed the finish line together, four arms raised in triumph.

“As long as they can see you, you give them something to chase,” King said. “But once you disappear, the doubts start to creep in.”

• • •

It wasn’t long before Elias was the one receiving instead of giving the food and extra wheels. In 1987, she placed 43rd in the Tour. After taking a year off for the U.S. Olympic trials, where she finished 13th, Elias placed fourth in the 1989 Tour, and earned the blue jersey for accumulating the most points of any racer. VeloNews magazine named her its women’s cyclist of the year.

Back home, Elias was honored in the State House for her efforts in cycling and her work against asthma. She discussed cycling in classrooms, in full uniform and with bike in tow. Newspaper editorials praised her not just for her success, but for her modest demeanor.

“I loved it,” Elias said of the attention. “It inspired me. It gives you that little extra to go on, like ‘Hey! Somebody cares about this!’ And that helps you when you’re training and it’s 50 degrees and you’re cold and you’re muddy and you’re wet and you didn’t want to go out that day, but it’s like, ‘I have to. I have to do it.’”

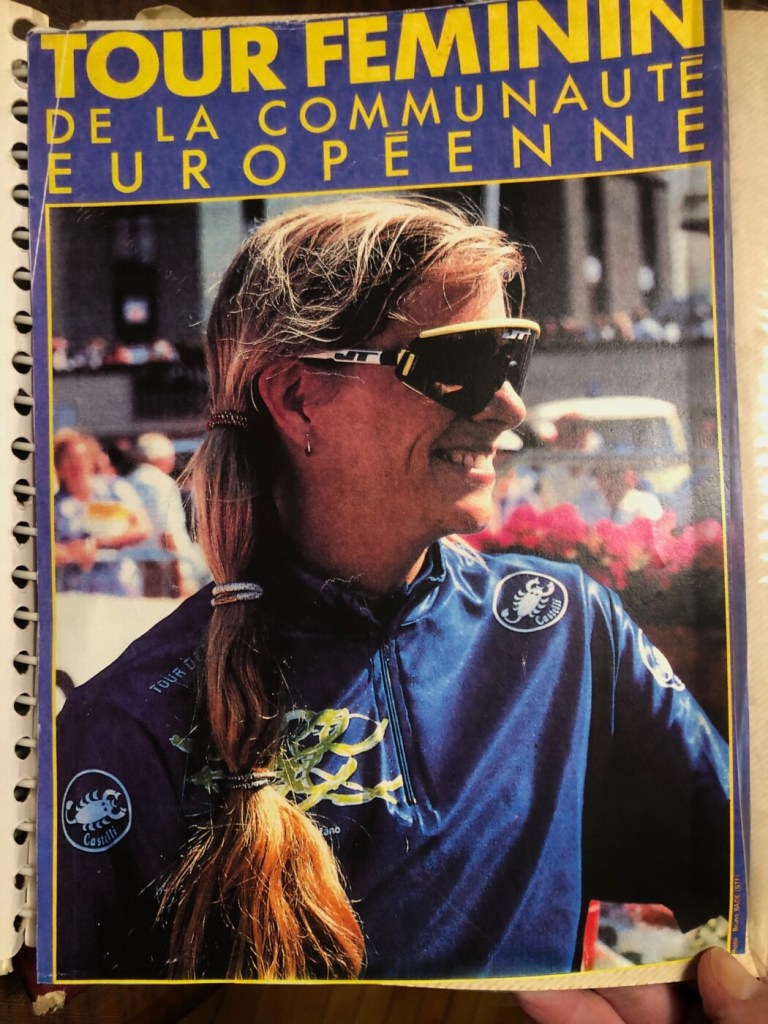

Susan Elias is all smiles at the Tour de France Feminin in 1989, wearing the Maillot a Pois (Mountain Jersey) after having placed second in the prologue. Elias, a Readfield native, is a former bicyclist who was recently elected to the Maine Sports Hall of Fame. Photo provided by Susan Elias

But Elias’ experiences in cycling went beyond the races and acclaim during what she called “some of the best times of my life.”

The Alps. The French countryside. The spectators along the streets with wine and cheese, watching women race by and exclaiming, “Oh, c’est la filles!” Carcassonne, a double-walled city in the south of France.

“You miss a lot,” Elias said. “You take it in, kind of in a blur, and it’s just like a memory snapshot. But every now and then, we did get to stop and tour a little.”

Of course, not everything was glamorous. While the men’s cycling teams traveled in big, comfy buses, Elias and her teammates had to cram seven riders and a team director into a Peugeot station wagon — with the bicycles stacked on top — to journey to each stage. In the days before in-ear coaching from team directors, Elias and King said, the cyclists would actually write key points on their arms during the race.

The money was far behind what the men were making — King said she received $100 for each stage she won at the Tour de France Féminin.

But in the end, the good outweighed the bad for Elias.

“The opportunity to travel to France and not as a tourist but as an athlete who is taken care of, was just some of the best experiences of my life,” Elias said.

• • •

By the early 1990s, Elias was ready to move on with her life. The Tour de France Féminin folded after 1989 for economic reasons, and succeeding attempts lacked the original’s stability, not to mention the official connection with the men’s Tour de France. And Elias never lost her desire to attend grad school.

And so she walked — or pedaled — away, with 20 race victories to her credit, passing up a chance of making the 1992 U.S. Olympic team.

“I think Susan quit a little bit sooner because she’d already been there and done that,” said King, noting Elias’s college accomplishments. “The problem with the Olympics is it’s every four years and it’s just kind of a long-odds lottery, and her career peak was not in one of those Olympic years.”

In 1994, Elias earned her master’s degree at Virginia Tech in wildlife science; that same week, she won a master’s road race in Georgia as she briefly came out of retirement to train another cyclist. She earned her Ph.D in Earth and climate sciences from UMaine in 2019.

These days, Elias’ biggest rivals aren’t other cyclists, but ticks. Since 2000, she has studied the ecology of disease-causing ticks and mosquitoes at the MaineHealth Institute for Research, and is often quoted in news stories concerning ticks and Lyme disease.

This publication shows Susan Elias at the Tour de France Feminin in 1989, wearing the Maillot a Pois (Mountain Jersey), after having placed second in the prologue. Elias, a Readfield native, is a former competitive bicyclist who was recently elected to the Maine Sports Hall of Fame. Photo provided by Susan Elias

Cycling isn’t completely out of Elias’ life, though. She frequently watches bike races on the Peacock streaming network. Last year, she reconnected with several contemporary riders in Paris for a Tour de France Féminin reunion, where she witnessed firsthand the progression her sport has made.

A new race, Tour de France Femmes, debuted last year, and the organizers have vowed to keep it going for the next century. The days of cramming eight people into a van are long gone; the women now have buses, with washers and dryers underneath in the cargo compartments.

While Elias said there’s still more room for improvement — more stages and challenging mountains would be nice, she said — she is amazed by the changes.

“We were just like, ‘Wow! We made it,’” she said.

And, of course, there’s her 1985 Colnago, a reminder of her short-but-remarkable career.

“I’m happy with what I did,” Elias said. I think you can always look back and say, ‘Oh, I wish I’d done this in this race.’ There’s a few regrets, but by and large it was successful and I got to meet good people and I got to travel all over. That was really my ticket to go see Norway and Japan and France and all over the United States … and understand what it takes.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story