As I began writing “Bayard Rustin: American Dreamer,” my biography of the 20th-century radical leader and activist, one of my colleagues cautioned me not to “fall in love.”

This, of course, is good advice for any biographer, and I tried to follow it.

But it wasn’t easy, because Bayard Rustin was America’s signature radical voice during the 20th century, and yes, I believe those voices includes that of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., whom Rustin trained and mentored.

His vision of nonviolence was breathtakingly broad.

He was a civil rights activist, a labor unionist, a socialist, a pacifist and, later in life, a gay rights advocate.

Today, scholars would call Rustin an intersectionalist, a man who understood the complex effects of multiple forms of discrimination, including racism, sexism and classism.

Early days and activism

Born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, on March 17, 1912, Rustin was one of 12 children raised by their grandparents. It is believed that his devotion to civil rights was formed by his grandmother, whose work with the NAACP resulted in leaders of the Black community, such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Mary McLeod Bethune, visiting the Rustin home during his Quaker upbringing.

Rustin was present at the creation of a host of pivotal American liberation movements. He helped found the Congress of Racial Equality and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, two civil rights organizations that were focused on ending the Jim Crow era of racial segregation.

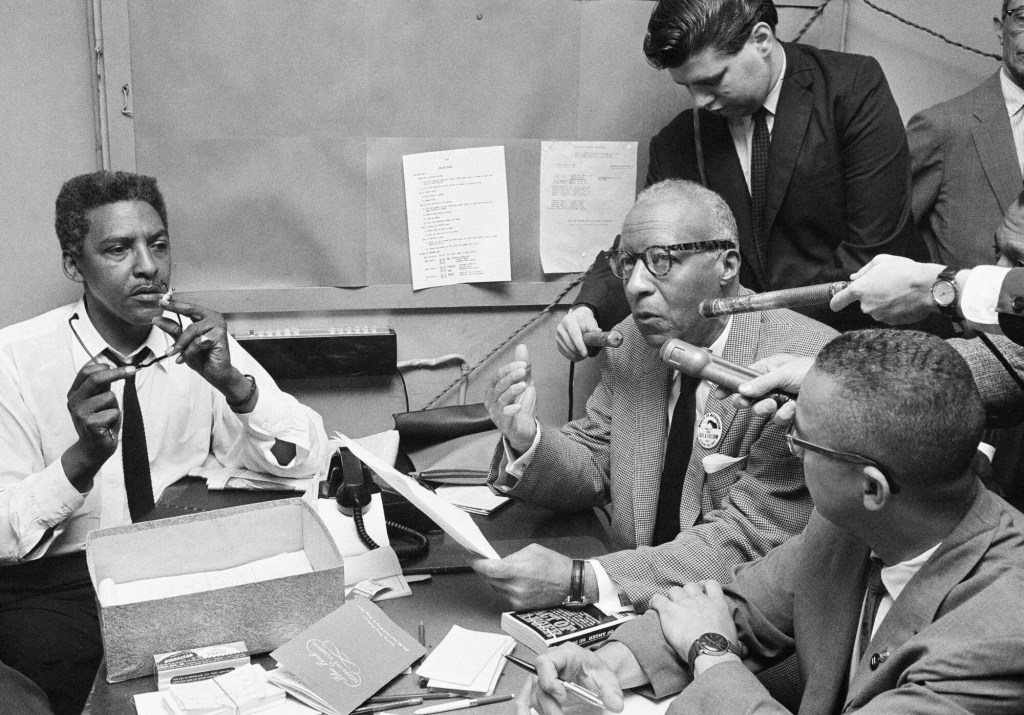

He worked with Black trade unionist A. Philip Randolph on the 1941 March on Washington Movement, which bore fruit in an executive order by President Franklin Roosevelt banning racial discrimination in the nation’s defense industries.

Rustin and Randolph worked again in 1948 on a successful campaign to end segregation in the U.S. military under President Harry Truman.

A pacifist, Rustin protested World War II by resisting the draft and, as a result, was imprisoned in 1944 as a conscientious objector.

After his release in 1946, Rustin became a major figure for the next two decades in two prominent pacifist organizations, the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the War Resisters League, both of which opposed the use of violence to settle disputes between individuals or nations.

In 1947, he and members of the Congress of Racial Equality planned the Journey of Reconciliation, the first organized effort to desegregate interstate bus transportation in the South.

Role in Montgomery bus boycott

Because of that work to integrate public transportation, Randolph suggested in 1956 that Rustin meet with a young preacher in Alabama who was organizing a bus boycott there.

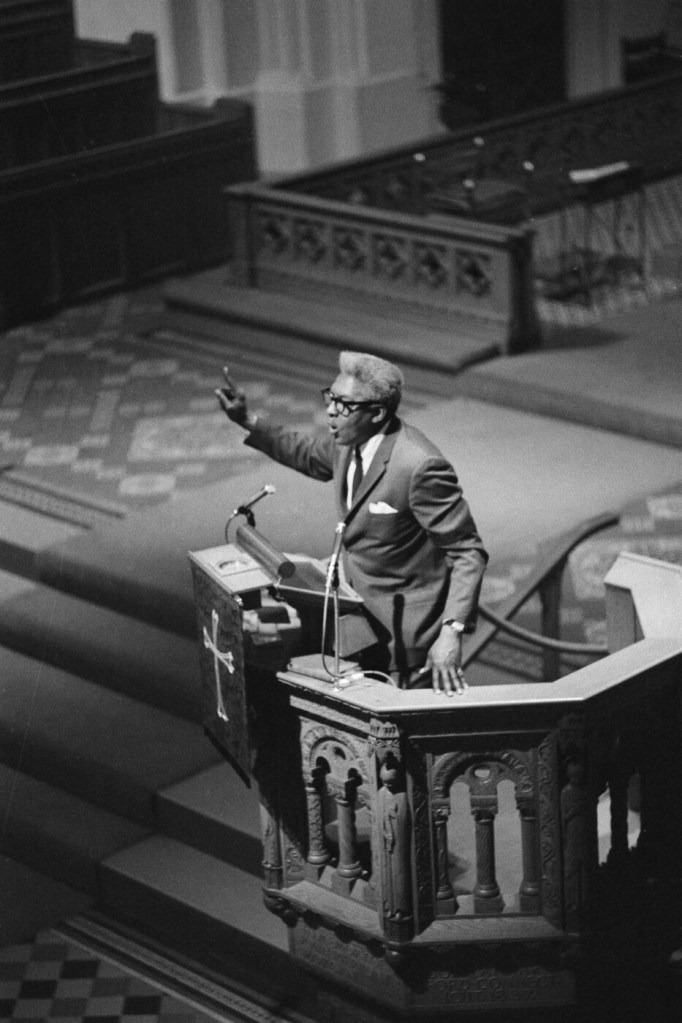

That meeting with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. during the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1956 changed both men forever.

From then on Rustin advised King on the principles of Gandhi and nonviolent direct action that – when combined with lawsuits, voter registration drives and lobbying efforts – ultimately led to passage of both the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

For Rustin, Black progress depended on politics and economics. To that end, in 1966 Rustin proposed the “Freedom Budget for All Americans” that promised every American employment, an income and access to health care.

His proposal became the template for progressive political activists in the 21st century.

Jobs and freedom

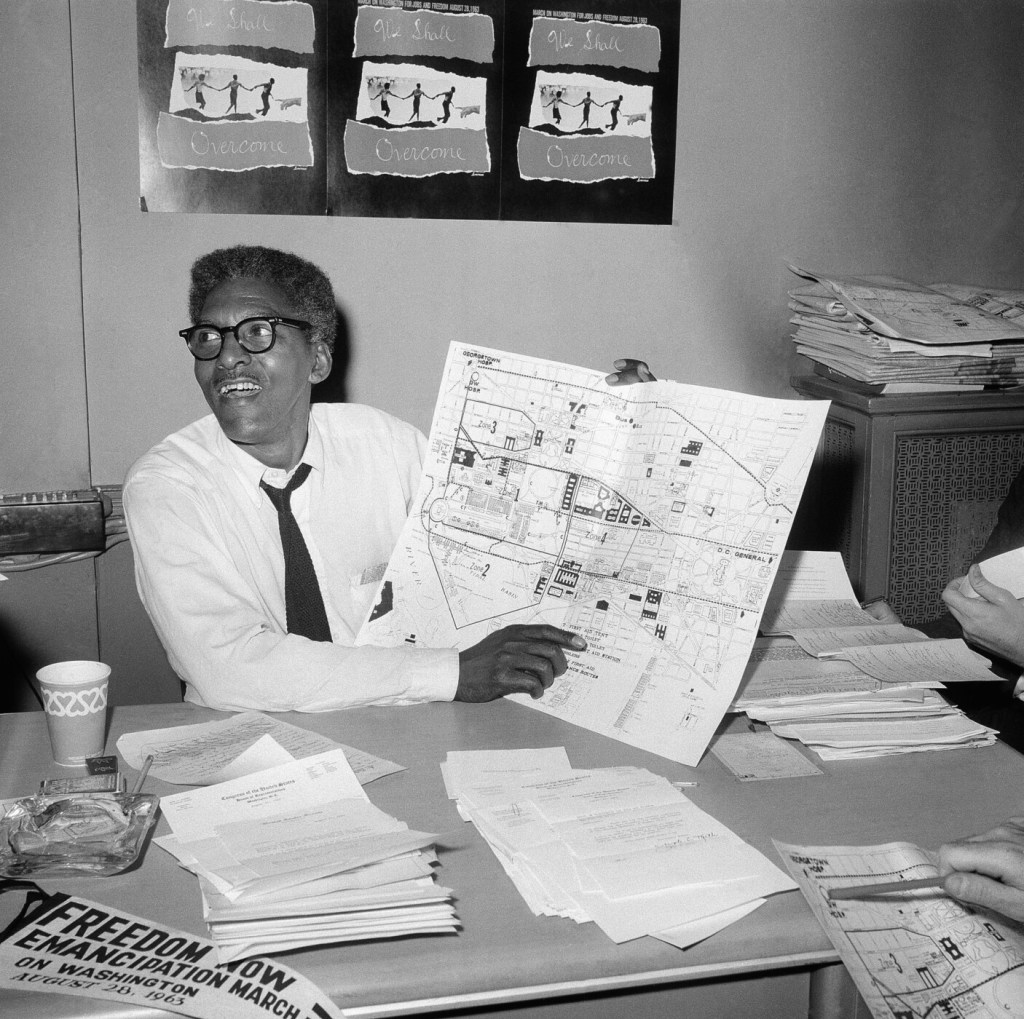

Rustin is best remembered as the organizer and orchestrator of arguably the seminal event in American civil rights history – the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

But it almost did not happen.

Rustin’s homosexuality had always been an issue, and not just to his opponents on the American right or to J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI.

Many progressive activists who were open-minded on matters relating to civil and labor rights were much less so when it came to Rustin’s sexuality.

Rustin had been fired by the Fellowship of Reconciliation after his 1953 conviction in Pasadena, California, on what was then known as a “public indecency” offense, involving sex with two other men in a parked car.

A few years later, King forced him out of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, fearful of the damage the issue of Rustin’s homosexuality could do to his organization.

It took the direct intervention of Randolph, Rustin’s lifelong friend and champion, to get King and other major civil rights leaders to agree to his selection as the organizer and orchestrator of the March on Washington in 1963.

Rustin then had to survive a denunciation by segregationist Sen. Strom Thurmond on the floor of Congress shortly before the march, during which the South Carolina lawmaker read from FBI reports on Rustin’s flirtation with communism – he had belonged to the Communist Party briefly as a young man – and his homosexuality and arrest in Pasadena.

But Rustin’s ability to organize was now too valuable to lose, and this time King stood by him.

As my research shows, King knew that only Rustin, who had spent the previous two decades leading demonstrations and walking picket lines, had the knowledge and experience to move 250,000 people in and out of Washington, D.C., on a hot summer day.

King also knew that Rustin could manage everything in between, including the order of the speakers.

By insisting that King be placed last on the program, Rustin ensured that King would have the final word and maximum dramatic effect. Though Rustin didn’t know it at the time, King’s “I Have a Dream” remarks eventually constituted one of the greatest speeches ever delivered in American history.

Rustin’s internal conflicts

The constituent parts of Rustin’s radical vision were often at odds and difficult to achieve, forcing Rustin into wrenching choices, as I learned during my research.

During World War II, for instance, he chose pacifism over the cause of civil rights when he refused to bear arms against a racist Nazi regime.

During the Vietnam War, he chose socialism over pacifism when he muted his criticism of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s policies in the hope of enacting his Freedom Budget for All Americans.

And in 1968, as a white-led teachers union and Black activists struggled for control of New York City’s public education system during the bitter Ocean Hill-Brownsville crisis, Rustin chose labor rights over civil rights and class over race as he lent his support to the union.

These choices cost Rustin allies and friendships, as former colleagues who afforded themselves the luxury of one-issue purity denounced him as an apostate, a hypocrite, a turncoat or worse.

But Rustin was none of those.

He dedicated his life to helping, as he put it, “people in trouble,” whomever and wherever they might be.

Accordingly, he put himself on the line for democracy advocates all over the world. They included African Americans, Latinos, working men and women, union members, the poor, war critics, anti-nuclear protesters, gays and lesbians, students, leftists, Soviet Jews, and Haitian, Hmong and Afghan refugees.

If those allegiances appear to be contradictions, in my view they were of the best kind.

Love for Rustin?

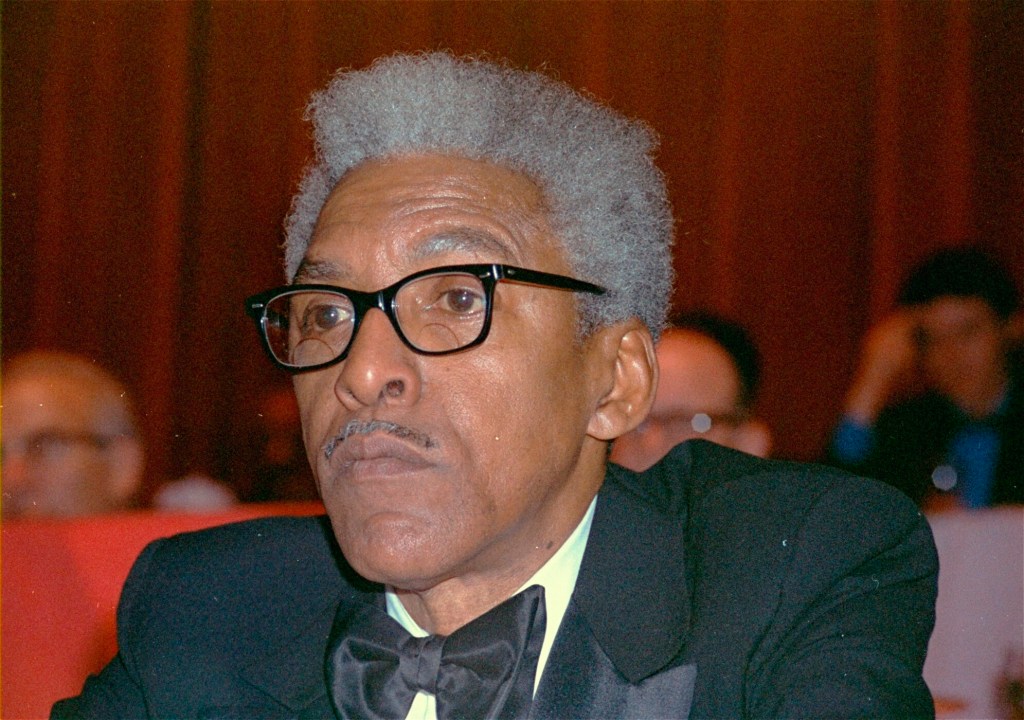

Above all else, Rustin chose to help people in trouble based on their condition, not their identity.

For that he has, if not my love, then my profound respect.

Of all the voices I’ve heard on my journeys through America’s 20th-century history, it is his that resonates most with me.

Rustin died in 1987, his radical vision unwavering until the end.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. The Conversation is an independent and nonprofit source of news, analysis and commentary from academic experts.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story