Jerry Hamza says that, for the last 35 years or so of his long career in show business, he was “like a store with only one customer.” He didn’t need or want any more.

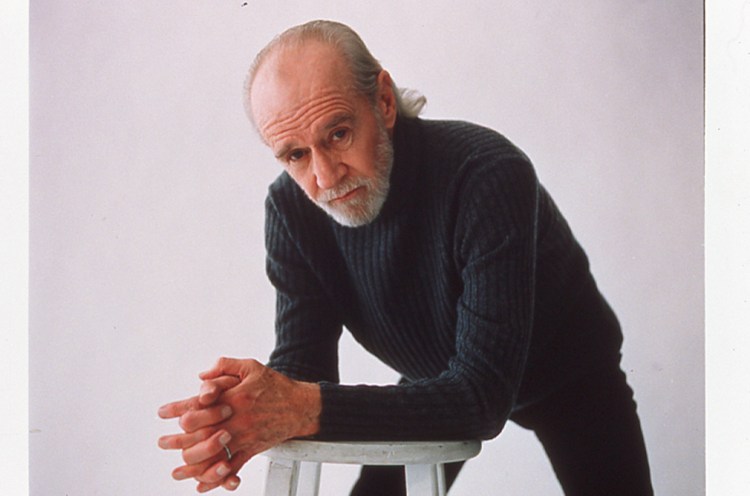

Hamza was a talent manager and his sole “customer” all those years was George Carlin, the groundbreaking comedian and social critic who rose to fame in the 1970s and influenced a couple of generations of stand-up comics. When Carlin died in 2008, Hamza retired to his home in the far eastern Maine town of Grand Lake Stream, but he kept working on Carlin’s behalf.

For years after Carlin’s death, filmmakers deluged Hamza and Carlin’s daughter, Kelly Carlin, with proposals to make a documentary film about the comic legend. But Hamza didn’t think any of them were right to tell Carlin’s full story and explain his legacy. So Hamza waited, patiently.

Then a few years ago, he got a call from a group he thought could do Carlin justice, which included director/producer Judd Apatow. That group, which included Hamza and Kelly Carlin as executive producers, made a two-part TV documentary movie called “George Carlin’s American Dream.” The film won the Emmy for best documentary in September and is streaming now on HBO Max.

“My hero in the business was Norman Granzs. He had one big star he managed for years and years, (singer) Ella Fitzgerald. He found a magical talent and protected her and nurtured her,” said Hamza, 80, from his home in Grand Lake Stream. “I felt the same way about George. He was a magical talent. I got close to him, and I didn’t want to work with anyone else.”

Jerry Hamza, right, with executive producer Teddy Leifer, after “George Carlin’s American Dream” won the best documentary Emmy in September. Photo courtesy of Jerry Hamza

WAITING FOR THE RIGHT TEAM

Hamza is a Rochester, New York, native who started coming to Grand Lake Stream to fly fish in the 1980s, to get away from the pressures of show business. He built the first of several homes there in the 1990s and has been living in town full time for about 14 years.

Over some 35 years of managing Carlin, Hamza came to not only respect Carlin’s talent but considered him a close friend. They spent countless hours together on tours or filming TV specials. Carlin was the best man at Hamza’s wedding. Carlin’s commentary on society’s ills could be caustic and cutting. He also dealt with his own problems over the years, namely alcohol and drug addiction. So Hamza wanted a film about Carlin to not only show his genius and his influence but his struggles as well.

Filmmakers who wanted to tell Carlin’s story knew they had to get the approval of Hamza – and Carlin’s daughter – since they controlled much of Carlin’s filmed work over the years. Hamza himself was producer of Carlin’s popular HBO specials, more than a dozen of them, from the late 1970s to 2008.

“Anyone who wanted to create something comprehensive about George had to get Jerry and Kelly’s support, since they controlled so much of the material,” said Michael Bonfiglio, who co-directed “George Carlin’s American Dream” with Apatow. Hamza was also interviewed for the film, and his unique perspective was very important to the story, Bonfiglio said. “He saw a side of George nobody else saw. They were close friends and spent decades on the road together. There weren’t a whole lot of people George was close to.”

A young George Carlin is seen in the film “George Carlin’s American Dream.” Photo courtesy of George Carlin’s Estate/HBO

The team that Hamza and Carlin’s daughter wanted to make the film was headed by producer Teddy Leifer, who has worked on several documentaries, including the recent streaming series “Once Upon a Time in Londongrad,” about 14 mysterious deaths in the United Kingdom with alleged ties to Russia. Also part of the team was Apatow, who has directed hit comedy films like “The 40-Year-Old Virgin” and “Knocked Up” but also produced a 2018 documentary about comedian Garry Shandling. Bonfiglio’s credits include the 2017 documentary “May It Last: A Portrait of the Avett Brothers.”

The film is nearly four hours long and uses old photographs, diaries, film footage, letters and dozens of interviews to tell Carlin’s story. It follows Carlin from his rough-and-tumble childhood in New York City to his early career as a conventional stand-up in the 1960s and his rise to international fame in the 1970s as a counterculture comedian parodying mainstream American life. His most famous routine from that period was about “seven dirty words” you can’t say on television. The film also chronicles his struggle with drugs and his relationship with his wife of 36 years, Brenda Carlin. Hamza is interviewed on camera as is Carlin’s daughter and his late brother.

Carlin was celebrated for pioneering intelligent observational comedy about the way people live. He was known also for his mastery of language and for routines that highlighted the power of words. His routine on the differences between baseball and football – and what the preference for football over baseball says about our society – is sometimes studied in high school and college English classes. Some portions of that routine include: “Baseball has the seventh inning stretch. Football has the two-minute warning. Football has hitting, clipping, spearing, piling on, personal fouls, late hitting and unnecessary roughness. Baseball has the sacrifice.”

About two dozen comedians and performers are seen in the film talking about how Carlin influenced them and changed stand-up comedy, including Jerry Seinfeld, Chris Rock, Stephen Colbert, Bill Burr, Bette Midler, Patton Oswalt and Jon Stewart. Carlin’s name and videos of his routines are often seen trending on Twitter and other social media, 14 years after his death.

“Teddy and Judd checked all the boxes we were looking for in filmmakers,” Kelly Carlin said. “I knew they would be unafraid to share the whole person and would be as creative and innovative as my father was. We did not want this to be a typical documentary.”

COUNTRY BEFORE COMEDY

Hamza knew very little about Carlin or his comedy when he first met him in the mid-1970s. In fact, he knew very little about comedy at all. He had spent about 10 years working for his father, who promoted country music concerts by artists like Hank Snow, Charlie Rich or Willie Nelson. His father’s company promoted concerts at venues around the country, including at Portland’s City Hall Auditorium before it was renovated and renamed Merrill Auditorium in the 1990s.

Around 1975, Hamza said he became burned out traveling the country to various country music shows and told his father he was quitting the business. A while later, Hamza’s father asked him if he’d handle just a few shows, by a comedian. His father told him the comedian had sold out some shows in Toledo, Ohio, but was “too loaded” and didn’t show up. But if somebody could get the comedian to his gigs, there was money to be made, his father said. The comedian turned out to be Carlin.

“My father said I’d just have to do these three or four shows with him. See how I like it,” said Hamza. “He was so brilliant and I liked him right away, but there were times he was so loaded during a show he’d just look up at the ceiling for 20 seconds and forget what the hell he was doing.”

Carlin battled addiction for years. In 2004, he announced he was entering a rehab facility to deal with his addictions, specifically to alcohol and the pain killer Vicodin.

It didn’t take Hamza long to realize he wanted to work with Carlin or for Carlin to realize he needed a steady manager with a good head for business to guide him. For about four or five years, until 1980, Hamza continued to promote country shows while also managing Carlin.

George Carlin, left, and Jerry Hamza at Hamza’s wedding in 2001. Carlin was best man. Photo courtesy of Jerry Hamza

By the late ’70s, Carlin wasn’t in the public eye as much as he had been earlier in the decade. Steve Martin had burst onto the scene and stolen Carlin’s spot as the hot comedian of the moment. So Hamza decided to pitch the idea of Carlin starring in his own live stand-up show to fledgling cable network HBO. The network agreed and Carlin did his first special in 1978. He did more than a dozen HBO specials over some 30 years.

“I think HBO had like 40,000 subscribers then. (HBO executive) Michael Fuchs loved George’s material and saw how important George could be to building the network,” Hamza said.

Hamza says Carlin was a prolific writer of jokes and routines. He wrote a lot of jokes Hamza thought were bad. But many of his routines were as much about making people think as making people laugh. Once they were driving together and were talking about the homeless crisis. When they passed a golf course, Hamza said something about how somebody ought to build houses for the homeless there. Carlin wrote one of his more memorable routines around that idea.

Hamza had grown up fishing in upstate New York but pretty much gave it up when he began managing Carlin and moved to California. His son encouraged him to take up fishing again in the 1980s, as a way to to put show business out of his mind. That’s when he started coming to Grand Lake Stream, known around the country as a picturesque and remote spot with great fly fishing.

Carlin also loved coming to Grand Lake Stream, Hamza said. He didn’t fish but enjoyed exploring the area’s waterways by canoe, including West Grand Lake, where Hamza lives. Hamza remembers Carlin being fascinated by an eagle on one of those excursions.

Over the years, Hamza encouraged Carlin to branch out to reach a wider audience, in movies and on TV. In the 1990s, he played Mr. Conductor on the PBS children’s show “Shining Time Station” and was the narrator of the British children’s show “Thomas the Tank Engine & Friends.” By the end of his career, his fans included “hippies” from the ’60s and college kids who discovered him when they were toddlers in the ’90s, Hamza said.

Carlin had a history of heart problems going back to the 1970s. He died of heart failure in Santa Monica, California, in 2008, at the age of 71.

“I think what I miss about him most was all I learned from him. I could teach him practical things about business. But he was like an English teacher when it came to the language, and I could always learn something from him,” said Hamza.

Hamza was at the Emmy Awards in Hollywood in September when “George Carlin’s American Dream” won best documentary. He and others involved with it say they are proud the film won, but are happier still that it will help new generations discover Carlin and his work and his way with words.

“George didn’t consider himself a stand-up, he thought of himself as a writer,” Hamza said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story