The cover is detached. Several browning pages are, too. Some information is missing.

And it’s the best 35 bucks ever spent.

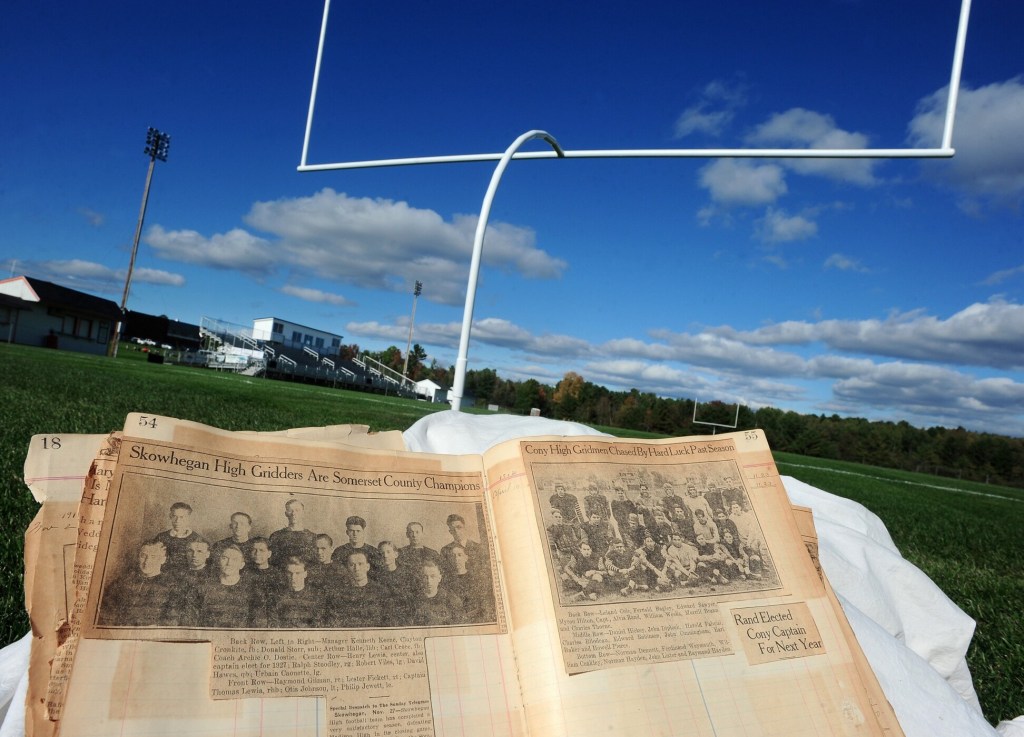

In 1926, a football superfan in Maine meticulously chronicled the state’s high school and college gridiron adventures in a thick scrapbook. On the cover, in very faded white letters, you can barely make out the title: “FOOTBALL 1926.” When one (gently) removes the cover, the reader finds more than 150 pages of newspaper clippings, all concerning — you guessed it — football.

Six years ago, I searched “Maine Football” on eBay, hoping to find something cool like an old University of Maine jersey or program. Instead, I found a listing for an ancient scrapbook filled with Maine-related football articles and photos. The return address: Framingham, Massachusetts. The asking price: $35.

Let’s see … spend my cash on a football scrapbook or some groceries? Needless to say, the chicken, milk and eggs had to wait a few days.

What I received in the mail surpassed my wildest expectations: This wasn’t a football book, this was a time capsule. Articles. Photos. All-Star teams. Assorted tidbits. Season summaries. A full chronicle of a season none of us alive experienced firsthand.

Most of the clips appear to come from the Guy Gannett family of papers: the Portland Press Herald, the late, great Evening Express and the Portland (later Maine) Sunday Telegram.

Many of the clippings, as you might imagine, are loose, and it’s a minor miracle they didn’t get lost. Some appear to have never been pasted down in the first place.

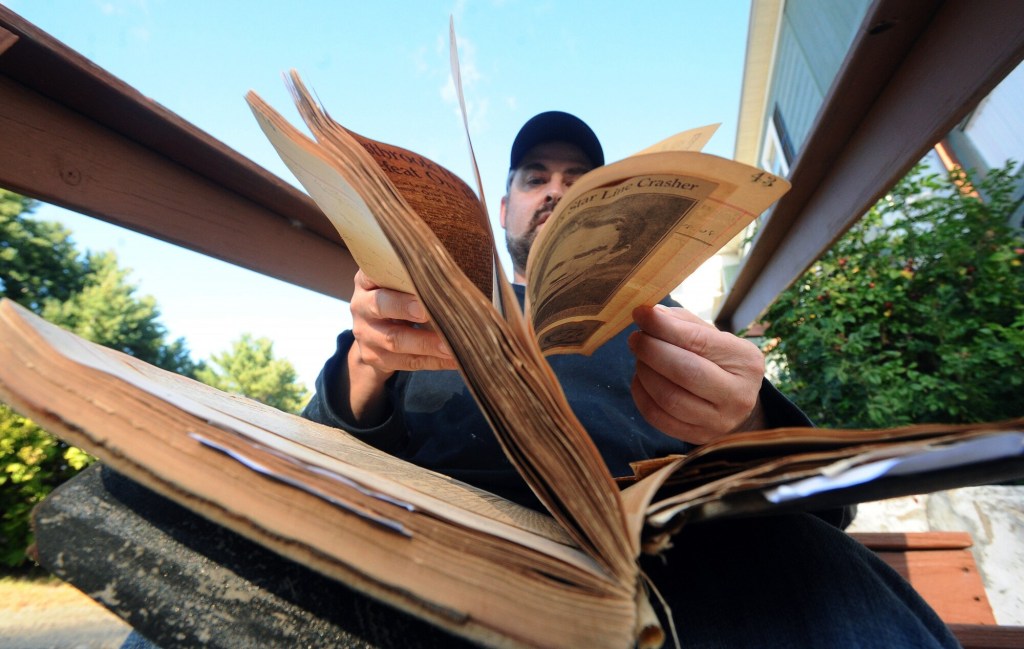

Kennebec Journal staff writer Dave Bailey flips carefully through the yellowing pages of a 1926 newspaper clipping scrapbook that he purchased on eBay. The book contains pages of newspaper clippings from Maine high school and college football teams in 1926. Bailey is shown at his Augusta home on Thursday. Rich Abrahamson/Morning Sentinel

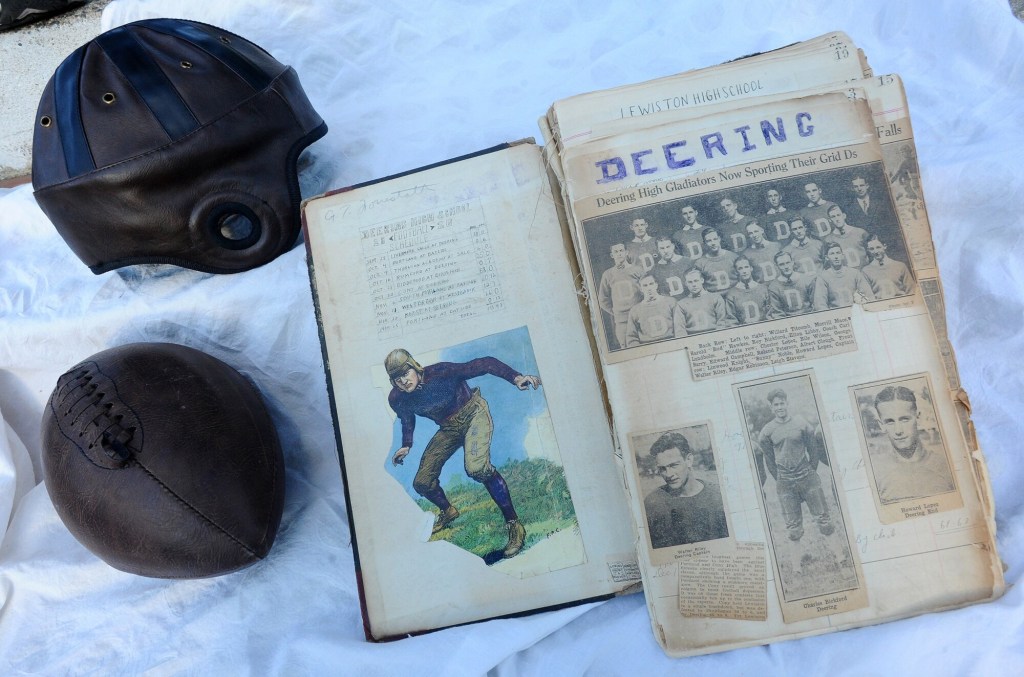

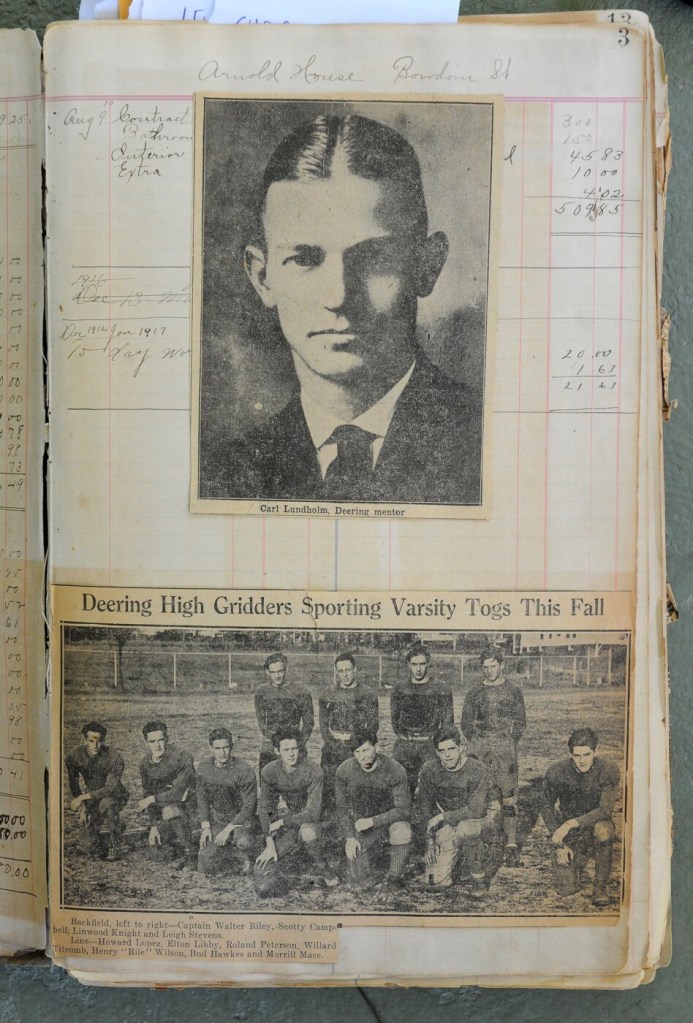

The book is divided into “chapters,” with every few pages devoted to a particular school. The guess here is that the book’s original owner attended Deering High in Portland, because the inside cover has an illustration of a purple-clad player just below the schedule and results (Deering went 7-3 and outscored its opponents 195-38). Furthermore, the book’s first 18 pages are devoted to the school.

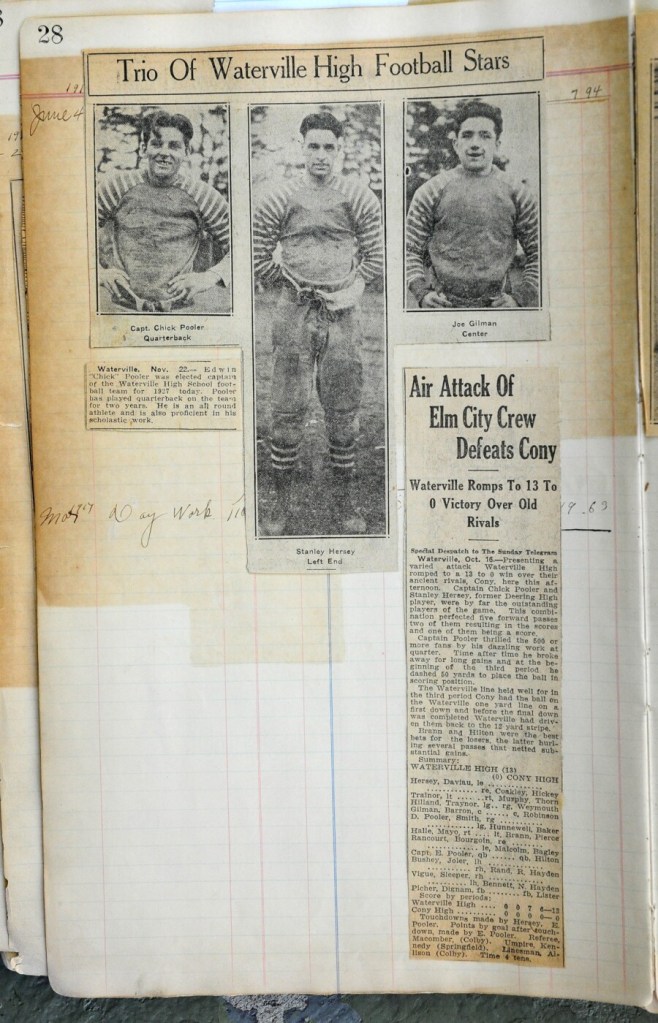

After Deering, comes Lewiston, Waterville, Sanford, Portland, Westbrook, Skowhegan, Cony. It’s easy to notice high school football in the 1920s was reserved for the big boys. Eight-man teams and co-operative programs need not apply.

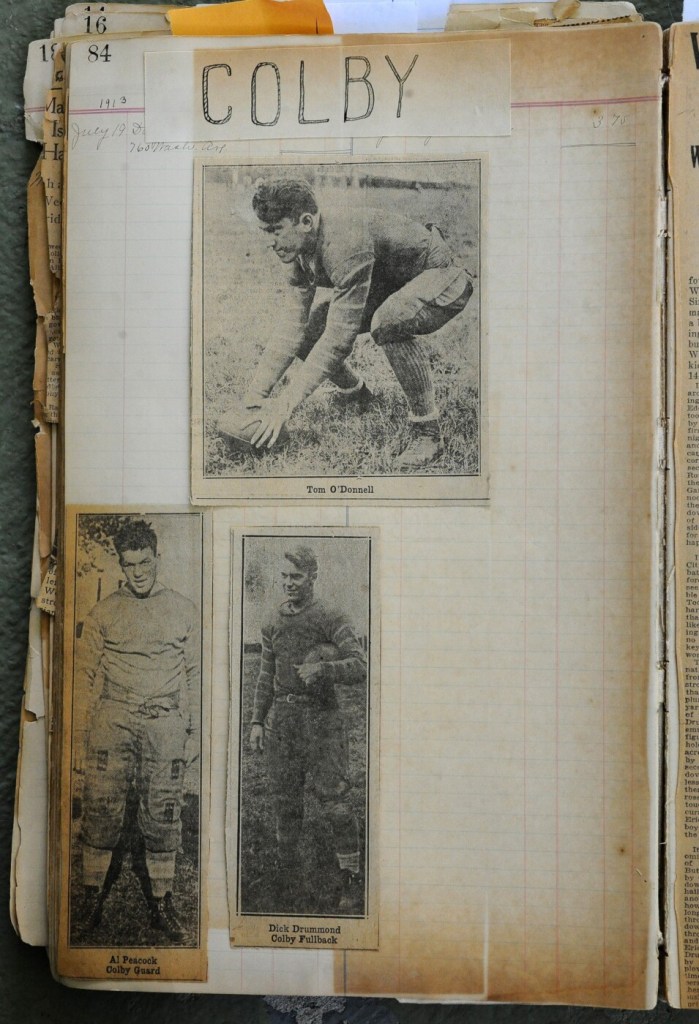

The college teams, led by the University of Maine, also get their due. Several pages are devoted to Maine’s 21-6 season-ending victory over Bowdoin. (As crazy as it sounds now, that was a big rivalry game for decades, often drawing upward of 10,000 fans.) Bates, Bowdoin and Colby also get some love, along with prep schools such as Maine Central Institute and Bridgton Academy.

The book concludes with clippings of large college games (ah, the days when Boston College-Holy Cross would pack old Braves Field), how-to columns, Grantland Rice prose and other oddities (Babe Ruth in a football uniform?).

If you’re looking for pro football, forget it. The NFL was still going through birth pangs and the New England Patriots were just a gleam in the eye of a young Billy Sullivan.

Sullivan owned the Boston Patriots franchise in the American Football League from 1960 until its sale as the New England Patriots in the NFL to Victor Kiam in 1988.

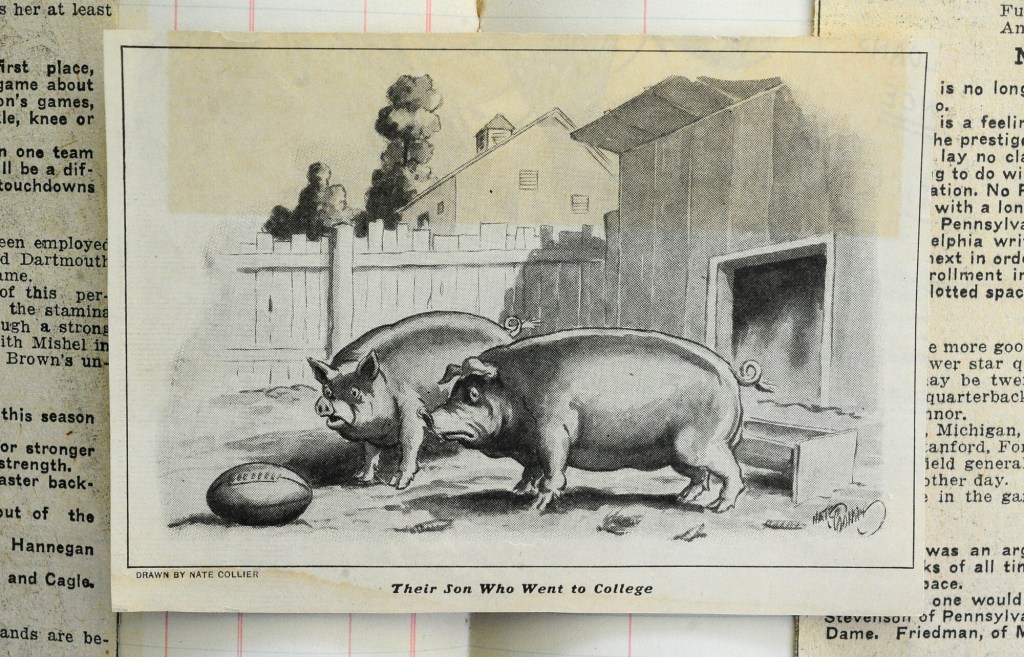

This cartoon was part of a collection of old newspaper clippings that comprise a 1926 scrapbook, which Kennebec Journal staff writer Dave Bailey purchased on eBay. The book contains pages of newspaper clipping from 1926 Maine high school and college football teams. Rich Abrahamson/Morning Sentinel

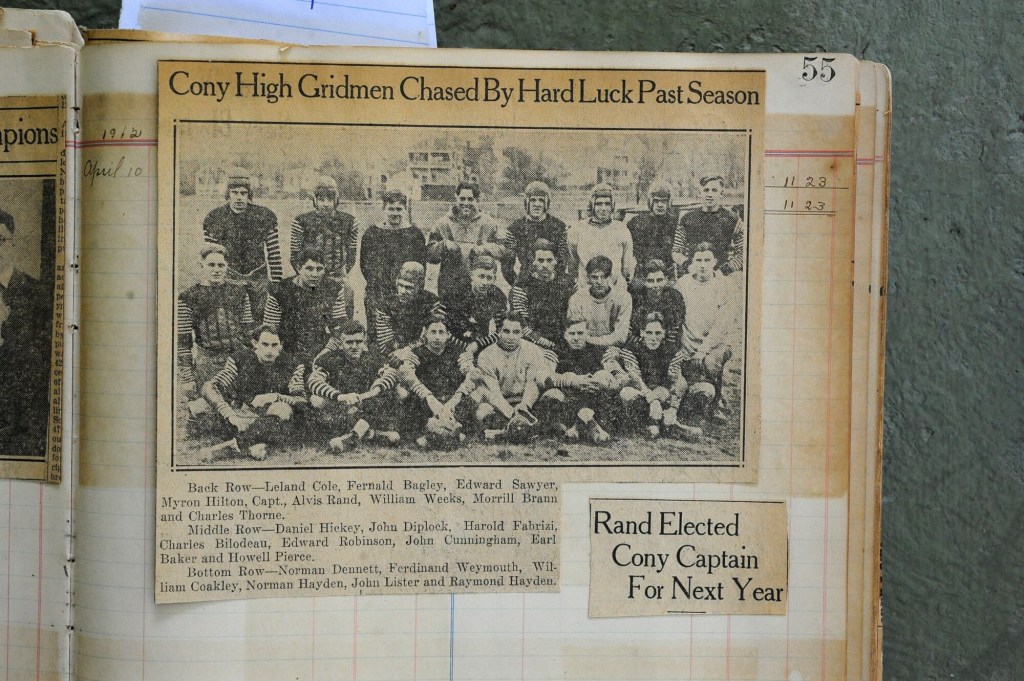

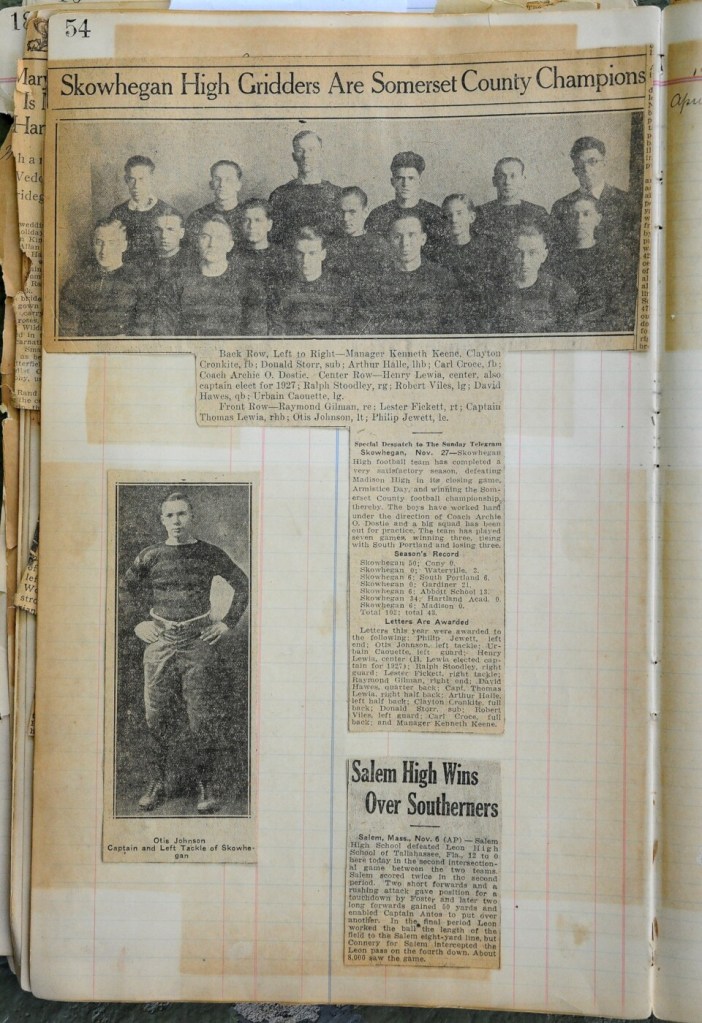

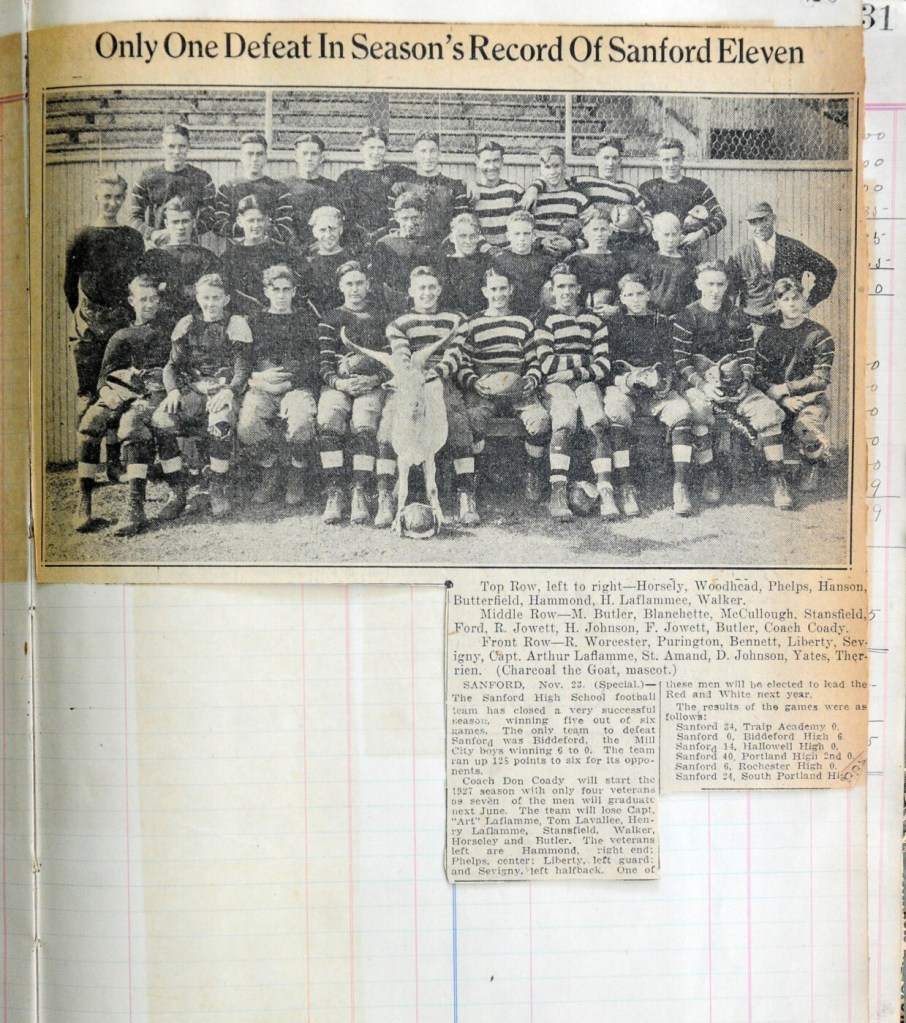

Upon going through the book, one is struck how football and journalism have changed over the last 96 years. The footballs are fat, the pads are thin and the helmets are made of leather. The jerseys have no numbers on the front and the ones on the back are often rudimentary. The “best” uniforms might go to Skowhegan, whose jerseys featured horizontal black-and-orange loops, making the players look more like pumpkins than athletes. At least they match; the Cony team photo shows players wearing a mishmash of game jerseys, practice shirts and sweatshirts.

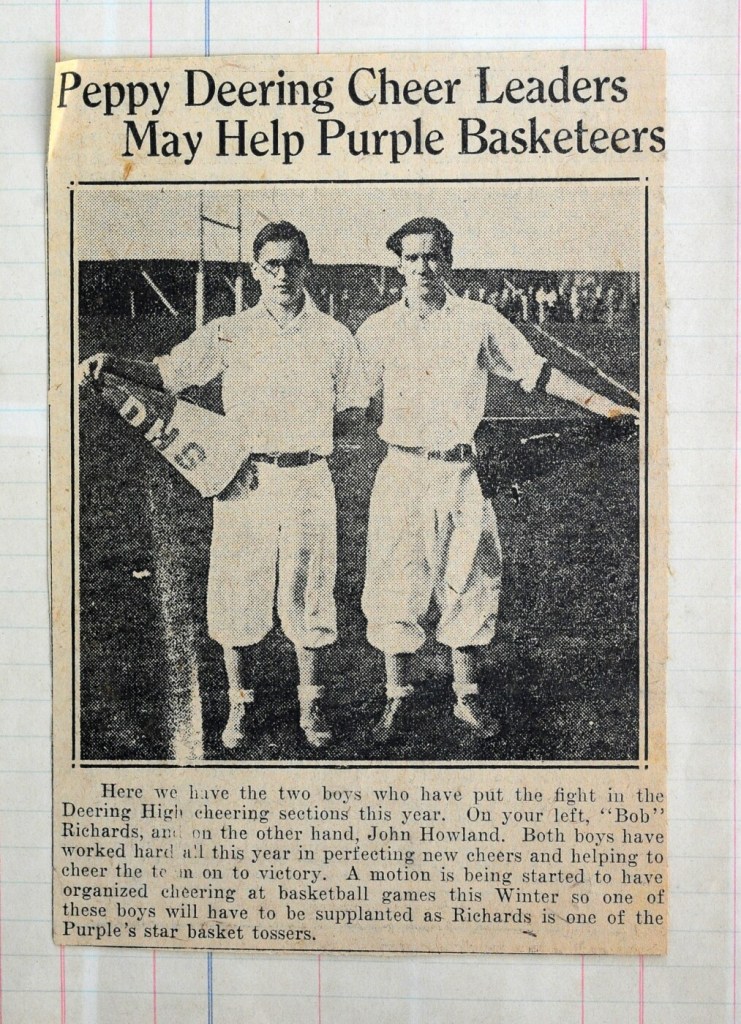

Even the cheerleading uniforms are strange; a photo shows two Deering cheerleaders in baggy golf pants. One is holding a giant megaphone.

Few schools had nicknames then, beyond their school colors. Lewiston, now the Blue Devils, was known as the “Blue Streaks” (maybe the coach talked a blue streak to his players in practice?) and South Portland’s Red Riots were called the “Capers,” a moniker used today for nearby Cape Elizabeth High.

The printed game recaps tend to be long and wordy, with detailed play-by-play, blow-by-blow accounts. The game story for a Maine-Bowdoin game, for example, takes up two pages in the book, followed by several pages of photos and other info. Remember, there were no TV highlights then, and even radio was in its infancy. No one’s face was buried in a phone looking for tweets on the Skowhegan-Gardiner game. The local papers WERE the sports media in 1926 Maine.

And some of the articles were, well, colorful. Take this lead from the Oct. 22 Bowdoin-Colby game, won by the Polar Bears, 13-7:

“The long lean finger of Lady Luck was pushed into a White Mule’s eye at Whitter Field Saturday afternoon. It was pushed once and withdrawn. The Colby Mule, temporarily blinded, staggered on, recovered, swept to the lead, and then ran into that finger again and was blinded for good.”

I think the writer is trying to say Colby had a run of bad luck.

The headlines are also unique:

• “As Colby Crunched The Bobcat Underfoot, 14 To 0, Brother Battles Brother, And Action Rules The Day”

• “Blue Streaks Show Crushing Power In Downing Game Fighting Fitzmen By Line-Smashing Game to 13-6 Tune”

• “Deering Completes Its Only Forward Pass” (Remember, teams in the 1920s threw that fat ball about as often as the moon changed phases.)

A scrapbook purchased on eBay by Kennebec Journal staff writer Dave Bailey contains pages of newspaper clippings from 1926 Maine high school and college football teams. This page features Skowhegan, which won a Somerset County championship. Rich Abrahamson/Morning Sentinel

The action photos tend to be quite good, considering the limitations of 1920s photography. While some pictures feature players leaping for the ball, others make you wonder what’s going on in that mass of humanity. In the background, fans often line the field in front of rickety wooden fences.

As previously noted, team photos received plenty of space. The one for Sanford High features a live goat mascot named Charcoal posing with the players (hope he didn’t eat the playbook).

There are plenty of wonderful tidbits scattered throughout:

• Portland High end Jimmy Maguire being ruled ineligible because he turned 21(!).

• Farmington Normal School, a forerunner of today’s UMaine-Farmington, fielded a team and went 5-2-1, mostly playing high schools, prep schools and alumni teams.

• A note on how “modern” athletes got to drink water “out of paper cups from a specially constructed container” instead of “an old fashioned pail.”

• A cartoon of two pigs staring at a football with the caption, “Their Son Who Went to College.”

Some of the names may ring a faint bell nearly a century later. Deering coach and athletic director Carl Lundholm’s name graces the gymnasium at the University of New Hampshire, his alma mater. UMaine end Rip Black was a bronze medalist in the hammer throw at the 1928 Olympics; his football coach, Fred Brice, is memorialized in the Brice-Cowell Musket presented to the winner of the Maine-UNH football game. Portland coach Jimmy Fitzpatrick is the “Fitzpatrick” in Portland’s Fitzpatrick Stadium and the James J. Fitzpatrick Trophy, given annually to Maine’s top high school senior player.

Oh, and who won the state high school title — and there was only one champion in those days, compared with today’s six? Lewiston wrapped up its third straight undefeated season to claim the 1926 crown, as playoffs didn’t happen until the 1960s. The Blue Streaks outscored their foes, 199-19. On the other extreme, poor Morse High went 0-7-2 and was outscored 97-6.

The game has changed. Journalism has changed. Even the schools have changed. But one constant has remained: Whether in 1926 or 2022, fans in Maine can’t get enough football and continue to savor every score, every big play, and every championship.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story