When asked to describe what was different, Deb Hawks Kelley kept her answer simple: Everything.

After a year studying abroad in France, Kelley returned to Colby College in Waterville in the fall of 1969. She was eager to begin her senior year.

When Kelley left, Colby was a place of old-fashioned attitudes, and traditions were the norm. Women were expected to wear skirts to dinner. Social life revolved around fraternities and sororities.

Now, back from the University of Rouen in France, Kelley looked at the Waterville campus and felt as if she was at a new, foreign school.

“When I got back to Colby, it had changed considerably,” Kelley said. “I found it very hard culturally to come back from France and go to a Colby I didn’t really recognize.”

For the class that came of age during what was arguably the most turbulent academic year in Colby’s history, it makes sense that the 50th reunion would be on hold as the world wrestles with a new crisis in the coronavirus pandemic. Colby sent students home in mid-March and has finished the semester through remote learning.

In recent days, the Waterville college has been holding virtual celebrations instead of an in-person commencement ceremony as the virus outbreak continues to force sustained lockdowns in Maine and across the globe.

But it is not the first time Colby has seen intense disruption to the end of its academic year and traditional commencement ceremonies. The class of 1970 experienced such disruption in its own way, too.

Like universities across the country, Colby was changing in the late 1960s and changing quickly. The Vietnam War was years old with no sign of slowing down. Rather, the war was intensifying, and with that, opposition to the war intensified, too.

There was mounting tension and turbulence during the decade, from the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, to the buildup in Vietnam, to the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, and the riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

“Colby is a liberal arts school, but I don’t think we were that liberal. We were white, privileged kids and the war was not really real to us,” said Ben Kravitz, president of Colby’s student government in 1969-70. “Then, it changed.”

During the 1969-70 academic year at Colby, tension reached an apex, culminating with a student strike in May that led to the cancellation of classes over the final weeks of the semester, and a subdued graduation ceremony that evokes strong reactions 50 years later.

It was a drumbeat of bad after bad after bad after bad. Mark Zaccaria, a Colby senior in the spring of 1970, asks how they could not have felt disillusioned and let down.

“That all led to this overwhelming sense that everything we’d been told about government was simply not true,” Zaccaria said. “Kent State was the exclamation point at the end of a long, run-on sentence.”

On May 4, 1970, during a rally protesting the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia, the Ohio National Guard shot and killed four unarmed students — Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, Sandra Scheuer and William Schroeder — at Kent State University.

“Kent State sort of stung everybody across the country,” said Earl Smith, Colby’s associate dean of students at the time. “The whole country was enraged.”

“Vietnam, it wasn’t just scary. It was wrong. It was useless,” said Joan Katz, a member of the Class of 1970 who organized protests in the fall and helped spur the student strike in May that effectively shut down the campus.

Kravitz remembered sitting in the basement of his Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity house, waiting for his draft number to be called. Vietnam was the first war on television every night. No wonder there was so much emotion, Kravitz said.

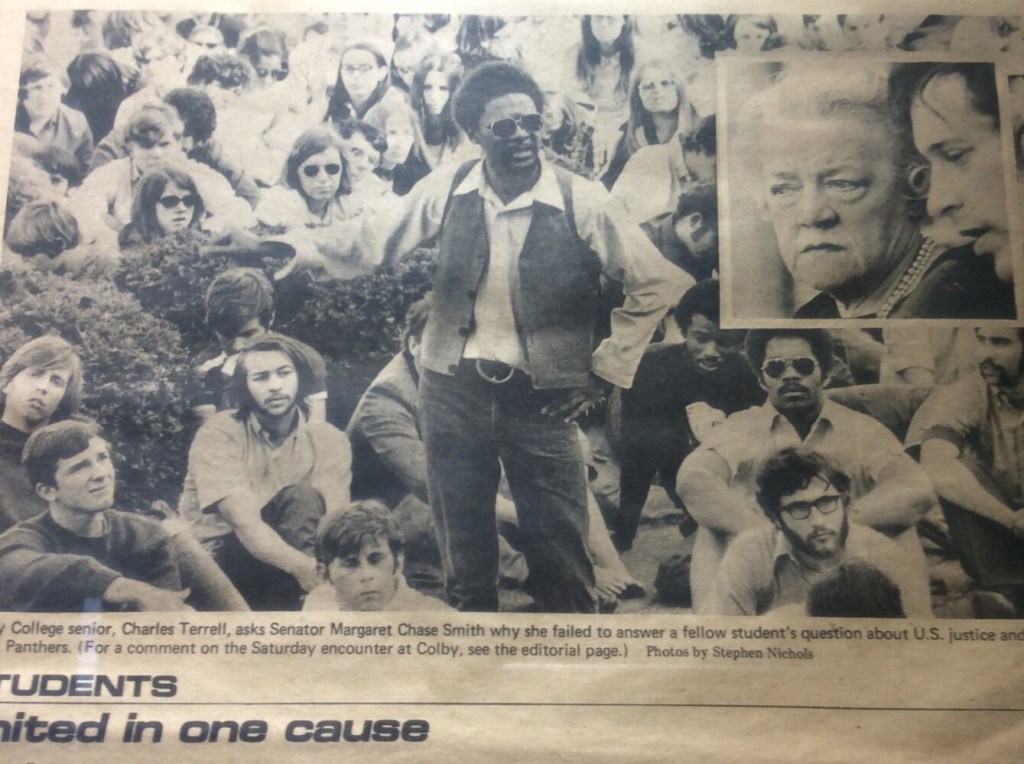

In this photograph from May 10, 1970, Charles Terrell confronts U.S. Sen. Margaret Chase Smith when she spoke to students at Colby College six days after four students were killed by Ohio National Guardsmen at Kent State University in Ohio. Photo provided by Charles Terrell

One of Maine’s U.S. senators, Margaret Chase Smith, came to Colby on May 10 to speak to students from colleges from around the state who were no longer just angry, they were fed up. Charles Terrell, a Colby senior, still has a copy of the photo taken of him that day, standing in a group of sitting students, confronting the senator.

“As one of the few black students on campus,” Terrell said, “things stood out in a very distinct way for me.”

Earl Smith remembers the cars arriving from schools across the state, full of students from other schools looking for answers. He remembers all the marijuana smoke in the air, and things not going particularly well for Sen. Smith.

“She stuck by Nixon too long,” Smith said.

“She came to settle us down,” Kelley said. “She was pretty famous. She was respected. I knew she was a force to be reckoned with.”

By that point, there was no settling down anybody. At Colby, where anti-war marches were held in the fall, and where the Students Organization for Black Unity staged a weeklong occupation of Lorimer Chapel in March, Kent State was the last straw.

REUNIONS POSTPONED

All Colby class reunions scheduled for this June have been canceled, as large gatherings worldwide were called off in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

For the Class of 1970, a group whose four years on Mayflower Hill culminated in a social hurricane, the reunions have been a time to quietly reflect. But mostly they have been a time to get together and tell happier stories.

“You go back to tell all ‘the old lies,’” Zaccaria said.

Perhaps those “lies” will get told next year. One of the ideas floating around Colby is to invite the classes that missed out on reunions this year to come back next year. There’s plenty of logistical questions that need answering. Can Colby handle twice as many people at once and still provide the top-shelf reunion experience alumni expect? Can Colby schedule a second reunion weekend and not interrupt the usual cycle of summer conferences and camps that take place on campus?

Katz has served as the Class of 1970’s reunion committee chair, with Kelley and Zaccaria presidents of the class. They spent a lot of time planning the reunion with Colby’s alumni office, but know it cannot go on this summer. Understanding why it cannot go on does not lessen disappointment.

“I don’t think I’ve missed a reunion,” said Katz, who has spent a career in social work. “Colby does such a great job with reunions. We have a great committee.”

“It’s such a letdown for us,” Kelley said. “Having to go to next year’s, it’s going to be fine.”

Kelley taught French and Spanish for 34 years. After retiring from teaching, she put her language skills to work as a concierge at the Mariott Long Wharf in Boston.

That hotel hosted the biotech company Biogen’s conference in late February, which turned out to be the site of an early cluster of coronavirus cases in the United States. Kelley was laid off in March.

Charles Terrell has never been to a Colby reunion. That was not a decision born from spite for his alma mater.

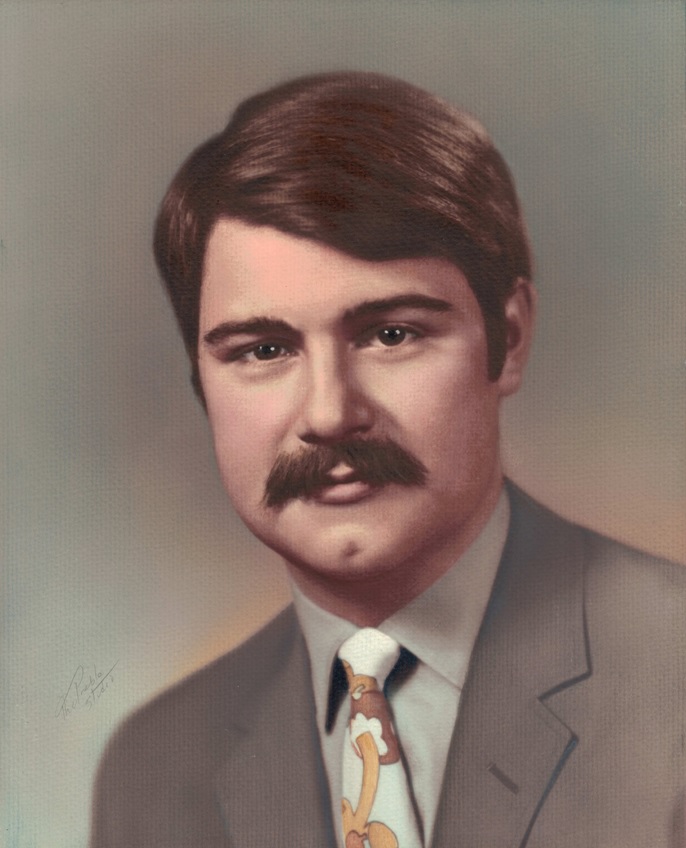

Mark Zaccaria during the 1969-70 academic year, his senior year Colby College. Photo provided by Mark Zaccaria

Terrell has found other ways to visit Colby in the 50 years since he graduated, and he knows he left a mark on the school while he was a student.

PUSH FOR GREATER DIVERSITY

Terrell did not set out to become an agent of change his senior year at Colby. Terrell had been active in student politics his first three years, serving as vice president of his freshman class and president of his sophomore and junior classes.

By the time he was a senior, Terrell was living off campus, at an apartment on Front Street, where his landlords were George and Mary Mitchell, the parents of future U.S. Sen. George J. Mitchell.

“They were wonderful,” Terrell said.

Terrell was working two jobs, including overnights at radio station WTVL. Between his studies and work, Terrell did not think he had time for politics. A visit from Sebsibe Mamo changed everything.

Mamo was a track and field standout at Colby who had competed for Ethiopia in the 1964 and 1968 Summer Olympics. Mamo wanted Terrell to take part in the formation of a new student group, the Students Organization for Black Unity, also known as SOBU.

Terrell knew black and Latin students needed a greater voice on campus. When he arrived at Colby in the fall of 1966, Terrell was one of 10 black or latino students in the class. In the spring of 1970, only two of them remained to graduate, he said.

Terrell agreed to meet with black students, and he found their energy, their passion, infectious. He would take part in SOBU, but when it came time to elect officers, Terrell made it clear he had no interest in serving in any capacity. An established leader, Terrell was nominated, then elected president of the group.

The main goal of SOBU was to help minority students thrive at Colby. For many, coming to Waterville, Maine, was a culture shock. SOBU implored the college to do more to help minority students in terms of orientation when they arrived on campus. They urged Colby to hire more black and minority professors.

Just 30 years old and closer in age to the students than most of the administration, Earl Smith agreed with the goals of SOBU.

“Colby wasn’t ready to deal with it, in terms of how those students were going to come to Maine,” Smith said. “They had some issues the college hadn’t thought about. Isolation, very little black faculty. It was hard for them.”

The main issue SOBU wanted changed was the policy dealing with scholarship students, most of whom were minorities. At the time, students on scholarship had to maintain a certain grade point average to retain their scholarship. For example, Terrell said, if the standard were 2.4 and you earned a 2.3 GPA for the semester, your scholarship was null and void. For many minority students, that meant they were leaving Colby, unable to pay tuition on their own.

“We’d seen so many of our classmates have to pack up and leave,” Terrell said.

It was not that SOBU had a problem with high academic standards; it was just the opposite. It wanted those standards to apply to every student, not just those on scholarship.

STAGING A SIT-IN

A year later, Colby’s administration would drop the GPA requirement for scholarship students, but in the spring of 1970, SOBU’s request to discuss the issue was not heard. Feeling a larger statement was needed, Terrell and SOBU leaders decided to organize a sit-in, where they could take over a campus building to draw attention and force the issue.

Taking over an administration building would draw notice, of course, but it would also draw more ire than they intended. Taking over the administration building would invite conflict.

But Lorimer Chapel? That would work. Taking over the chapel, a place for quiet reflection, would not disrupt the day-to-day life at Colby and would show President Robert E. L. Strider and the rest of the college’s administration this was a peaceful demonstration.

At about 8:30 on the evening of March 2, 1970, 17 members of SOBU began their occupation of Lorimer Chapel. Led by Terrell, the students issued their demands to Colby’s administration, faculty and students. The following morning, Strider responded to SOBU in writing, but Terrell said he does not remember Strider coming to speak face-to-face.

“Strider did not visit us in the Chapel, nor did he send anyone else, if memory serves,” Terrell said.

A portion of Strider’s letter to SOBU is published in “A People’s History of Colby College,” posted on the college’s website, and stated the college could not “engage in the most useful kinds of discussion under the present circumstances.”

“The occupation of a building occasions the disruption of normal college activities, and, as long as you are obstructing the normal use of Lorimer Chapel, you are engaged in illegal trespass,” Strider wrote. “If it is approach to your stated goals that concerns you most, you can signal this by leaving the chapel and talking with some of us about real approaches to these goals.

“If you remain in the chapel, it will appear that your concerns are more with the notoriety of your action and with the atmosphere which could easily be established through continued occupation.”

As student government president, Kravitz did his best to keep the sides talking.

“I tried to be a go-between between the students and administration. I tried to moderate,” Kravitz said. “Strider took it as a personal attack on him. He wasn’t interested in meeting with students. I’d come out with (SOBU) to address the press. I viewed my position as independent.”

SOBU had support from much of the campus community, Terrell said. He remembers it being quiet most days. They would greet the campus by blasting the music of The Temptations in the morning.

“I thought it was a very courageous thing to do,” Smith said of SOBU’s Lorimer Chapel occupation. “It divided the place. There were people who thought they had a point. There were others who didn’t. … Strider was very understanding, but he had a sense of law and order.”

On May 9, a week after Terrell and SOBU went into Lorimer Chapel, Colby was granted a restraining order, giving the school the right to evict them. The order was delivered to the Chapel by the Maine National Guard, Terrell said, with the promise from the Colby administration that no punishment would come if the students complied. Terrell went back inside and convinced his fellow students that their point had been made, and it was time to leave, peacefully, as they had entered.

“After a week, we walked out with our heads held high,” Terrell said. “It was peaceful, and I’ve always been really proud of that.”

Charles Terrell, right, leaves Colby’s Lorimer Chapel after he convinced his fellow protesters the Students Organization for Black Unity had its point staging a weeklong sit-in March 1970. Terrell has since served as a trustee of the college and was a member of the committee that hired the college’s current president, David A. Greene. Submitted photo

As graduation approached in May, Terrell faced a consequence of his actions. He had spent so much time away from class, Terrell was failing French. He needed to retake the course in the summer so he could go on to graduate school at Boston University. Retaking the course would cost $500 that Terrell did not have.

Terrell went to Earl Smith, explained the situation, and asked if Colby would loan him $500. Instead, Smith gave Terrell the money, with a stipulation: Remember what Colby gave to you, and give back as much as you can.

Terrell served as a Colby trustee and was on the search committee that hired current president David A. Greene. Higher education was Terrell’s life’s work. He earned a doctorate in higher education and spent time as a dean of students at Boston University and director of financial aid of BU’s medical school. He now does pro bono work with Cross Creek Associates, providing students with free financial aid information.

If anything, Terrell’s relationship with Colby was strengthened by his experiences as a senior.

“I’m on campus two or three times a year, every year,” Terrell said.

Smith confirmed Terrell’s recollection.

“I was a young pup. I was closer to the age of the students than the ones running the show,” Smith said. “I was close to a lot of students.”

ESCALATION IN WAKE OF KENT STATE

As protests continued and escalated throughout the academic year, Zaccaria felt the student body dividing into three groups. A third of the students were radicalized, he said, and at the other end of the spectrum, a third were horrified by what they considered to be a societal breakdown. The third in the middle, where Zaccaria saw himself, were just mentally exhausted and trying to tune out the noise.

Zaccaria was a member of Air Force ROTC and had a commission awaiting him when he graduated.

“Like it or not, I got permanently assigned to one side of the debate,” said Zaccaria, who served five years of active duty in the Air Force, first in pilot training then as a flight instructor, before going into his family’s shipbuilding business.

“I myself was a little bit shell-shocked by the whole thing. As someone who was perfectly committed to playing by the rules, I was just confronted by the dichotomy of what I always believed and what my lying eyes were telling me.”

If anyone expected the tension on campus to ease as the semester ended, Kent State made that impossible.

On May 8, 1970, The Colby Echo student newspaper covered Colby student government’s reaction to the Kent State shootings. A few days earlier, the National Student Association, of which Colby was a member, declared a student strike to protest the invasion of Cambodia.

Initially, Katz proposed Colby students engage in a two-day boycott of classes. According to the Echo, that measure failed by a 14-9 vote. Student Government then approved a vote to support the student strike.

Katz said she remembers an overall consensus in favor of the strike. According to the Echo story, there were just a half-dozen or so dissenters in the vote.

“I was involved in the anti-war movement during most of my senior year. I helped organize the fall 1969 march from Colby to the downtown space where we had a speaker from the Maine Times weekly as the main draw,” Katz said.

Katz felt she and her Colby classmates were not as radicalized as students on other campuses across the country. Colby did not have a chapter of Students for a Democratic Society, a group that organized large rallies and demonstrations. Kent State changed things.

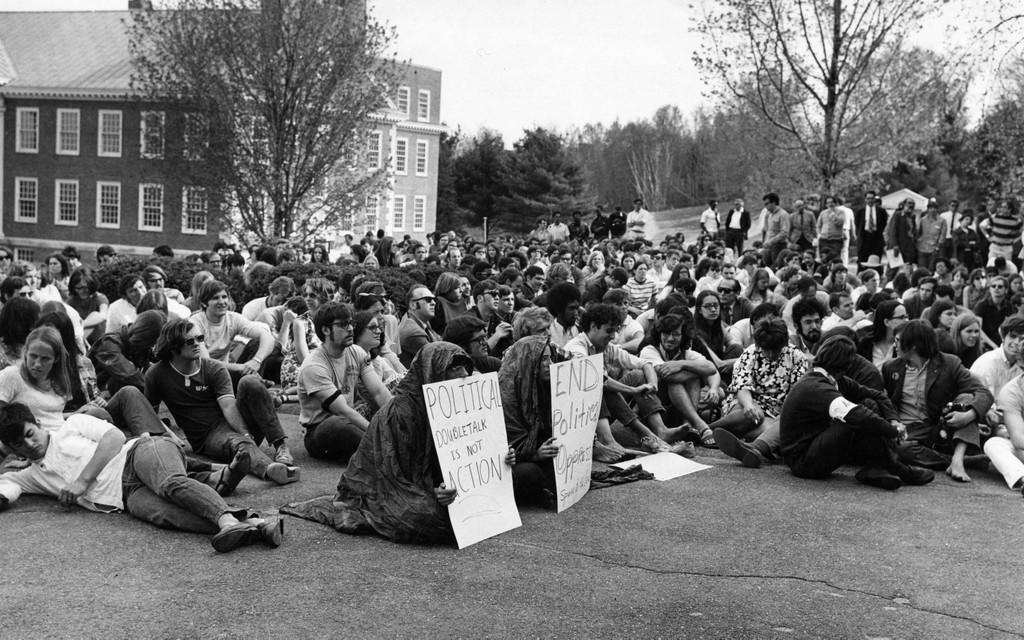

On May 6, 400 students took part in a march through downtown Waterville in memory of the four victims at Kent State and to protest the escalation of the war. At 11 a.m., students gathered at Miller Library to lower the flag in memory of the Kent State victims. At 2 p.m., they marched, leaving four mock coffins at the post office. Forty students began a two-day sit-in at the Colby ROTC office.

After the students voted overwhelmingly to support the nationwide strike, Colby faculty voted to support the strike, and the semester was effectively over.

Students from other Maine colleges and universities join Colby students in Waterville on May 10, 1970, to hear what U.S. Sen. Margaret Chase Smith had to say about the secret bombing of Cambodia, the war in Vietnam and the killing of four students six days earlier by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University in Ohio. Submitted photo

Graduation a few weeks later was an understated affair, with many graduates choosing to forego caps and gowns. Many of those who did wear the traditional garb did so at the insistence of their family, Kelley said, adding she wore a pale yellow sleeveless dress and matching coat. So much has been forgotten over the years, but Kelley always remembers what she wore that day that turbulent year ended.

“It’s your year, you’ve decided what to do with your future and everything is in turmoil,” Kelley said.

That graduation day is mainly remembered for the remarks made by Strider, who died in 2010. Strider felt the student strike and its support by the faculty was a black mark on Colby’s academic character, and he let that be known in his graduation remarks to the Class of 1970, telling them that their diplomas were not as valuable as those earned by other Colby graduates.

“(Strider) was offended by what he perceived as a lack of decorum. He was disrupted by people not listening (to him). They were listening, they were just not buying it,” Zaccaria said.

RETELLING THE STORIES

That year was a low point for Strider, who served as Colby’s president from 1960 until his retirement in 1979. While he raised Colby’s academic profile in his two decades as president, in hindsight, Strider was unprepared to handle the unrest that hit Colby in the Vietnam era.

“He was a wonderful person. It was just an awful time to be a college president,” Smith said. “It was putting a scholar in a street-fight, and that’s not a good thing.”

Many feel Strider’s remarks are a major reason the Class of ’70 has consistently been one of the lower-ranked classes when it comes to Colby alumni fundraising. Kelley thinks the reason has more to do with careers chosen by many in the class. So many graduates went into fields such as social work and education. The Class of 1970 was not full of people who went into the business world and made lots of money.

Even so, 50 years has softened Katz’s feelings on Strider. “He was overwhelmed by this, and a lot of other presidents were too,” Katz said.

The 50th reunion would be a chance to retell these stories, all the “old lies,” to borrow a phrase from Zaccaria. There are a half-century of new stories to tell, too, and that’s what the Class of 1970 feels it will miss if a reunion is unable to go off next year.

When he was a younger man attending reunion weekend, Kravitz took note of the added attention given to the 50th reunion class. When all the classes would make their way from a reception at the president’s house to another event, the 50-year alumni would hop into golf carts and get rides as the rest walked. Kravitz watched the royal treatment and knew his time would come.

“Given the circumstances, I think it’s a minor inconvenience,” said Kravitz, who unlike many of his classmates had a long career in the business world, selling his Summit Tire of Massachusetts company a decade ago. “Whether we do it at 50 or 51 years is not a big deal to me.”

Like its senior year, the Class of 1970’s reunion is not coming easily.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story