Third of six parts

ELIOT — It was here, at William Everett’s tavern on the banks of the Piscataqua River, that Maine’s life as a separate colony began its end.

At 7 in the morning on Nov. 16, 1652, the townspeople of what was then Kittery gathered in the tavern on the orders of four commissioners from Massachusetts, who were sent to secure the local people’s submission to be ruled by Boston. Things turned acrimonious. A man named John Bursley was arrested for threatening the commissioners with violence. The proceedings lasted four days.

Massachusetts’ territorial claim was based on a novel reading of the charter Ferdinando Gorges and his associates had granted two decades earlier. The north end of the grant reached three miles north of the Merrimack “and to the northward of any and every part thereof,” meaning it followed that river’s meander through what is now south-central New Hampshire. Now the Bay Colony was claiming that this meant it controlled everything to a line extending from three miles above the headwaters of the Merrimack – in northern New Hampshire – all the way to the sea, including every English settlement in New Hampshire and Maine.

New Hampshire – created back in 1629 by Gorges’ business partner John Mason – had already capitulated. Now the Massachusetts General Court in Boston wanted the struggling settlements of Gorges’ Province of Maine to do the same.

Maine is celebrating its bicentennial of statehood, but the event marks not the birth but rather the rebirth of Maine as a separate entity. Its loss of independence in the 17th century proved decisive, an episode that made Maine a colony of a colony, with lasting effects on the state’s culture, economy and fundamental security.

AN INVENTIVE LAND GRAB

Massachusetts’ annexation drive came in the immediate aftermath of the English Civil War, which saw its allies triumph in London and Maine’s royal benefactor, Charles I, beheaded. During the war, the Maine settlements – a ribbon of coastal hamlets stretching from Kittery to the Kennebec with 1,200 inhabitants – had been orphaned. Supply ships stopped arriving. Gorges stopped writing them orders years before his death in May 1647. The residents of Kittery and several other towns drew up their own compact of government, elected a governor, and carried on as best they could. Those from Saco eastward stumbled through the war as the “Province of Lygonia,” named for Gorges’ mother, but flouting his authority.

After the English Civil War, Maine’s royal benefactor, King Charles I, was beheaded. The king is depicted with his wife, Henrietta Maria, in this period engraving. Photo courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery

Despite the chaos and privations, most Maine colonists were opposed to being annexed by their Puritan neighbors. “We are loath to part with our precious liberties for unknown and uncertain favors,” the southern settlements’ governor, Edward Godfrey, told authorities in Boston as he petitioned the English Parliament to protect Maine. The first commissioners sent to Kittery, in June 1652, were rebuffed. “We resolve and intend to go on till lawful power command us the contrary,” Godfrey informed their superiors.

COLONY: MAINE’S PATH TO STATEHOOD

Sunday, Feb. 16 – Chapter I: Dawnland

Sunday, Feb. 23 – Chapter II: Rivalry

Sunday, March 1 – Chapter III: Conquest

Sunday, March 8 – Chapter IV: Insurrection

Sunday, March 15 – Chapter V: Liberation

Sunday, March 22 – Chapter VI: Legacy

Prior to the November meeting at the tavern, Godfrey laid out a robust case against annexation, outlining fears about what it would mean for religious liberty in what was then an Anglican colony. At the meeting, townspeople asked that Massachusetts guarantee their rights and liberties in writing; the commissioners said they would do so only after the Mainers submitted to their authority. In the end, the attendees signed the Articles of Submission. They included John Bursely and a local woman, Mary Bachiler, who carried an infant and had an “A” branded on her for committing adultery, and likely had little love for Puritan justice. (She would serve as the inspiration for “The Scarlet Letter” by Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose ancestor, William Hawthorne, lived in Kittery.)

Detail of a 1784 map of “the County of York being part of the Province of Massachusetts Bay.” Nearly two centuries after the first colonization attempts, European-American settlement remained concentrated close to the coast and west of Pemaquid. Portland and South Portland were still part of a larger entity named Falmouth. Image courtesy of American Antiquarian Society

The commissioners moved on to Gorgeana. Two days later that town’s inhabitants also agreed to submit to Boston, including, mysteriously enough, Godfrey himself. “Whatever my body was enforced unto,” he later told Parliament, “heaven knows my soul did not consent unto.” To press salt into their wounds, the town was promptly assigned a provocative new name: York, site of a massive Royalist defeat in the recent war. In Wells one local man marched out of the meeting in disgust; the commissioners had him arrested and dragged before them to answer for contempt. He and his neighbors submitted that afternoon. By summer’s end, these three towns, Cape Porpoise and Saco were all incorporated into a new Massachusetts county named Yorkshire.

The Lygonian settlements to the east held out for six years, ignoring orders to appear before courts in York and Boston to submit to annexation. But in 1657 the Massachusetts General Court decided to play hardball, arresting three of Lygonia’s leaders, dragging them to Boston and threatening them with imprisonment to secure their submission. In 1658 the hamlets then known as Black Point, Blue Point and Stratton’s Island were annexed together as a new town named for Scarborough – site of another wartime Royalist debacle – and those around Casco Bay became Falmouth, after the North English town where the heir to the throne and his mother had been captured after a monthslong siege.

When Oliver Cromwell’s military dictatorship collapsed in England two years later, Ferdinando Gorges’ namesake grandson petitioned the new king, Charles II, to restore Maine to his family. He had some success when Maine was briefly absorbed into the new crown colony of New York in 1665, but three years later Massachusetts officials marched into Maine with a “troop of horse and foot” soldiers to reassert its control anyway.

The Gorges family gave up, sold their claim to the Puritan commonwealth and put an end to the resistance.

COLONY OF A COLONY

Maine became something unusual in British North American history: an unwilling colony of a colony, a place annexed by the victors of a bloody civil conflict, people with different religious, ideological and ethnographic characteristics. Our state is in many ways a post-colonial society, the result of more than a century and a half of rule by an external government that had its own interests, not those of the people living in Maine, foremost in mind.

There were undeniable advantages. Massachusetts brought far better order, security and infrastructure. It put an end to feudal institutions and introduced strong municipal governments. It brought Maine into the Yankee cultural milieu, with taxpayer-financed public schools, town commons and efficient government. It even granted Mainers greater flexibility than its citizens back at home, including allowing full citizenship to be granted to non-Puritans and greater tolerance of other religions.

But despite all of this, the colonial experience was on balance a disaster for Maine’s people, most of all because of the effect it had on relations with the Wabanaki.

Throughout the second half of the 17th century, the Wabanaki controlled the entire interior of what is now Maine, plus the coastline from the Penobscot eastward, which, on paper, was part of France’s Acadia colony. They outnumbered the European settlers, probably many times over. And they actively resisted intrusion in the river systems beyond the reach of salt water.

Before the annexations, this wasn’t a major flashpoint, a cool rapprochement having taken hold on the southern Maine frontier since the collapse of the Popham Colony. “The people actually living in Maine on both sides tended to have a live-and-let-live policy to get along,” says Emerson Baker, a historian at Salem State University who studies the period. “Fact is, we lived relatively peacefully without too many shots being fired in anger until Massachusetts came in.”

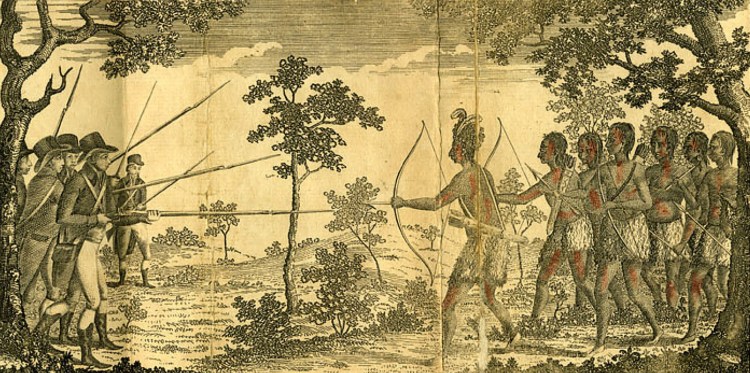

The Anglo-Wabanaki wars lasted a century and deeply scarred both parties. “A Narrative of the Indian Wars in New England” by William Hubbard, first published in 1677, was one of many English accounts of the bloodshed and, despite its errors, remained popular with Euro-American readers right into the early 19th century. Image from Open Library, edition published by William Fessenden, 1814

The Puritans took a dim view of the “wilderness,” a disorderly place at the edge of their fields where Satan lurked, ready to tempt those who strayed from the watchful eyes of the community. The people of the forests – the Pequots and Wampanoag of southern New England and Wabanaki to the north – were seen as being under devilish influence on account of their unrestrained manners, more open sexuality, belief in spirits and failure to observe the Sabbath. And because they were “savages,” the normal moral obligations – respect for treaties, fair dealing, protection for the innocent – did not apply.

Trouble had started soon after the Puritans’ arrival. In 1636, a number of them marched into the wilds to found a squatters’ colony called Connecticut. To do away with this competitor, Massachusetts authorities engineered a genocidal war against the Pequots to create a pretext to absorb the unorthodox settlements by conquest, burning women and children alive. Captured children were sold to slaveholders in the English Caribbean, a practice Puritan preacher William Hubbard condoned because they were “young serpents” whose removal was a sign of “Divine Favour to the English.”

WAR AFTER WAR

After the conquest of Maine, Massachusetts embarked on a series of genocidal wars, starting with King Philip’s War in the 1670s and extending, with only brief periods of peace, all the way to the conclusion of the so-called French and Indian War in 1763. Maine’s settlers were dragged into all of these conflicts and, among the Europeans, paid the steepest price.

King Philip, Sachem of the Wampanoags, as depicted in a hand-colored engraving by Paul Revere. Courtesy of Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery

“Massachusetts had these ideas about race that suggested to them that all Indians would band together, so when war broke out there they thought the Wabanaki would rise up too,” says Lisa Brooks, who is of Wabanaki descent and a professor of American Studies at Amherst College and author of “Our Beloved Kin,” a book on the first of these conflicts. “They issued orders to disarm Wabanaki people in Maine at a time when they were mainly using guns for hunting, causing people to starve in the winter.”

“It seemed so strange to the Wabanaki because there was no warfare up there,” she adds. “This policy was one of the main causes of the war up north.”

The Maine settlements were outnumbered and built on the scattered, West Country model, making them difficult to defend, so the Wabanaki were able to wipe out most of them in many of these wars. Between 1689 and 1713, every settlement east of Wells was wiped out, its inhabitants fleeing first to the offshore islands and then to Massachusetts proper, where the streets were often choked with refugees from “the Eastern territories.” Portland was a ghost town, with 200 bodies left piled on the southern foot of India Street and, in the words of 19th–century historian Nathan Goold, “exposed to the wild beasts and birds and the bleaching storms for two years.”

Baker, who has extensively researched the Puritan witch trials, discovered that many of those accused of witchcraft were refugees from Maine, including Portland’s former minister, George Burroughs, who was executed at Salem. Many of the judges had property in Maine. “If the native Americans, who in the Puritan world view were seen as being perhaps in league with Satan to begin with, are burning down your sawmills and trading posts, you ‘know’ that Satan has been set loose in your country,” Baker says. “So you do your job: round up the witches.”

Illustration of a witch trial in Massachusetts. Most of the “witches” were outsiders, refugees from Maine’s Anglo-Wabanaki wars. Image from Wikipedia: 1902 Illustration by John W. Ehninger

Those who avoided accusation returned to ruined farms and town sites in times of peace, only to have them destroyed again when the next conflict – many of them overlapping with Anglo-French wars – erupted. Growth and development was almost impossible, Maine being a war zone and killing field for the better part of a century, which explains why so much of even its coastline remained largely undeveloped well into the 20th century.

“There was war after war,” says Donna Loring, a former legislative representative for the Penobscot Nation who serves as an indigenous affairs adviser to Gov. Janet Mills. Loring estimates the Wabanaki population fell to just 8,000 to 9,000 by 1720, down from at least 30,000 in 1610.

Brooks has studied French transcriptions of tribal councils in this period and was struck by how, between the wars, the Wabanaki had tried to negotiate a sharing of the land. “Again and again the Wabanaki people tried to educate the English on how to live in their territory, where they could have their settlements and where they had to stay away from,” she says. “You had generation after generation doing this, even with all the devastation of so many wars and conflicts and diseases and resource depletions.”

As these wars began winding down in the 1730s and 1740s, however, a new source of conflict began to emerge, this time one that pit the Massachusetts elite against a new force: the backwoods colonists who were pushing the line of settlement deeper into the interior of southern and midcoast Maine. They were occupying lands the Wabanaki had been forced to retreat from, lands that were owned on paper by some of New England’s most powerful men. Neither side respected the claims of the other, sowing the seeds of insurrection.

Next Sunday: Insurrection

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story