Rena Heath learned the value of hard work growing up on a potato farm in northern Maine.

She raised livestock and canned vegetables for 4-H competitions and earned money baby-sitting. She started her teaching career in the 1960s and retired in 2004 as a receptionist at the Maine Attorney General’s Office, a job she enjoyed for 23 years.

Now, at age 82, Heath is among a growing number of older Mainers with limited incomes and little or no retirement savings who are increasingly dependent on taxpayer-funded programs and charity for everyday expenses and eventual long-term care.

With mounting health problems and dwindling financial resources, Heath finds herself struggling to make ends meet on her monthly $1,500 state pension. Her budget is so tight, she said, one friend pays for her cellphone line and another friend has promised to cover her funeral expenses.

The Hallowell resident recently faced the hard reality of her financial straits when she started checking out future long-term care options. She called a few assisted-living facilities to find out if they accepted residents who would be dependent on Medicaid, known as MaineCare here.

“Some I called don’t want charity cases,” Heath said. “There aren’t many places that do.”

Like Heath, about 40 percent of all Maine seniors who live independently are financially insecure, according to a national index. They cannot afford basic expenses – food, housing, transportation, health care or even cleaning supplies – without relying on benefit programs, loans or gifts.

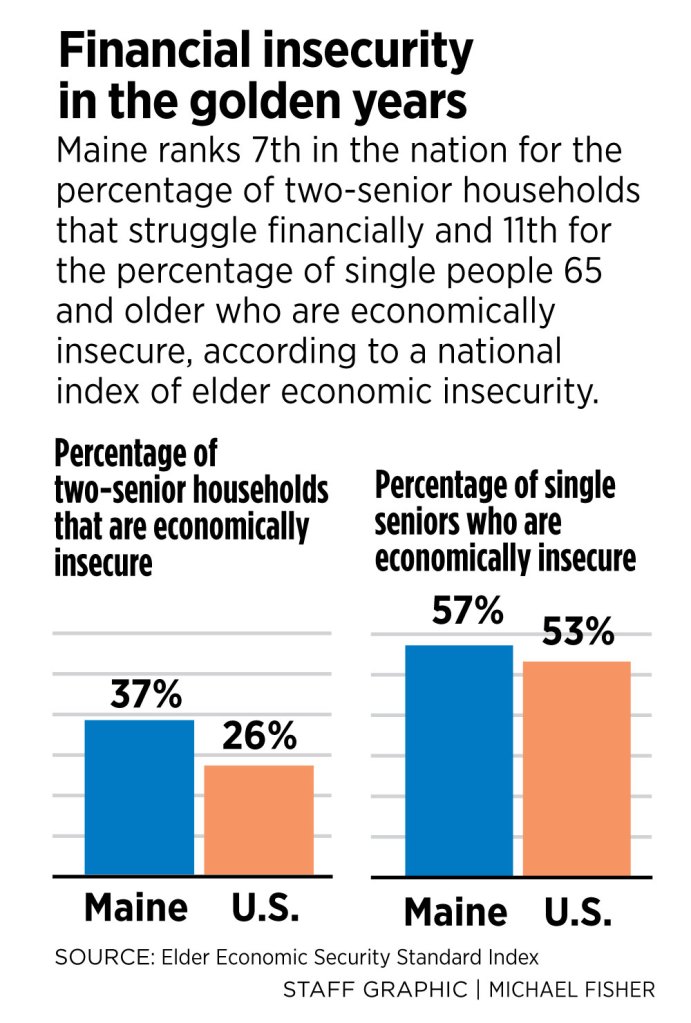

More than half of single Mainers age 65 and older, and about a third of two-senior households, are considered financially insecure.

Maine ranks 7th in the nation for the rate of two-senior households that struggle to afford basic expenses, and 11th in the nation for the rate of single seniors who are considered economically insecure.

The number of struggling Maine elders is only expected to grow as the state’s senior population continues to swell. Maine has the highest median age in the nation – 44.6 years – and ranks a whisper-close second to Florida for population age 65 or older – 20 percent. Maine’s senior population is projected to increase 42 percent in less than 20 years, from 266,241 people today to more than 379,731 in 2036, according to the State Economist’s Office.

The statistics put Maine on the front lines of a national retirement crisis that anticipates a $1 trillion to $14 trillion funding gap between the pensions and retirement savings that Americans have today and what economists say they will need to maintain their standard of living after retirement. Pressure is mounting on government and community agencies that step in when seniors can’t provide for themselves.

The cost of public assistance to Maine’s retired population – from food stamps to long-term care – is expected to increase from $35 million this year to $273 million in 2032, according to a University of Maine report by Philip Trostel. Nationwide, the cost is expected to increase from $7.6 billion to $65 billion in the same period.

Which is why U.S. Sen. Susan Collins is pushing two bills in Congress that would help Mainers save for retirement and encourage employers to offer work-based retirement savings plans.

Collins, a Republican who heads the Senate Aging Committee, spoke to the issue recently on the Senate floor. She noted that some recent retirees lost or spent their retirement savings during the 2008 recession. Many carry more debt than past generations. And because people are living longer, health care costs are rising along with the need for expensive long-term care.

She pointed to a recent Gallup poll that found only 54 percent of working Americans believe that they will have enough money to live comfortably in their retirement years. For most older Mainers, she said, Social Security makes up at least 90 percent of their income.

“I’ve heard from so many Maine seniors who say they are barely getting by,” Collins said in a recent phone interview. “We have a looming crisis now and more of our seniors are going to end up retiring into poverty or outliving their savings.”

THE ELDER INDEX

Nearly 75,000 senior households – or about 110,000 older Mainers who live independently – are financially insecure, according to the Elder Economic Security Standard Index.

That means at the end of each month, they have little or no money left for necessary home repairs, dinner at a restaurant, a weekend trip to visit grandchildren or larger looming costs such as assisted living or long-term care.

The Elder Index was developed by demographics experts at the University of Massachusetts Boston to provide a more complete picture of financial insecurity than federal poverty measures set by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Maine’s overall senior poverty rate is 8.1 percent, below the 9.3 percent national average. But that number doesn’t reflect households that are slightly above poverty level but unable to cover their basic expenses.

Applying Elder Index standards to Maine, 57 percent of single seniors and 30 percent of two-senior households are economically insecure, resulting in national rankings of 11th place and 7th place, respectively. Across the United States, 53 percent of single seniors and 26 percent of two-senior households have annual incomes below the index.

Such stark numbers spotlight mounting problems related to the rising demand and cost of health care, accessible housing, rural transportation, long-term care and other things older people need, especially in the United States, where the senior population is burgeoning as it is in many industrialized nations.

“For so long, the discussion around senior finances was (that) older people are all set. They have Social Security. They have Medicare. But it isn’t enough now and it won’t be in the future,” said Jan Mutchler, a demographics expert who worked on the Elder Index.

WITHOUT ANY EXTRAS

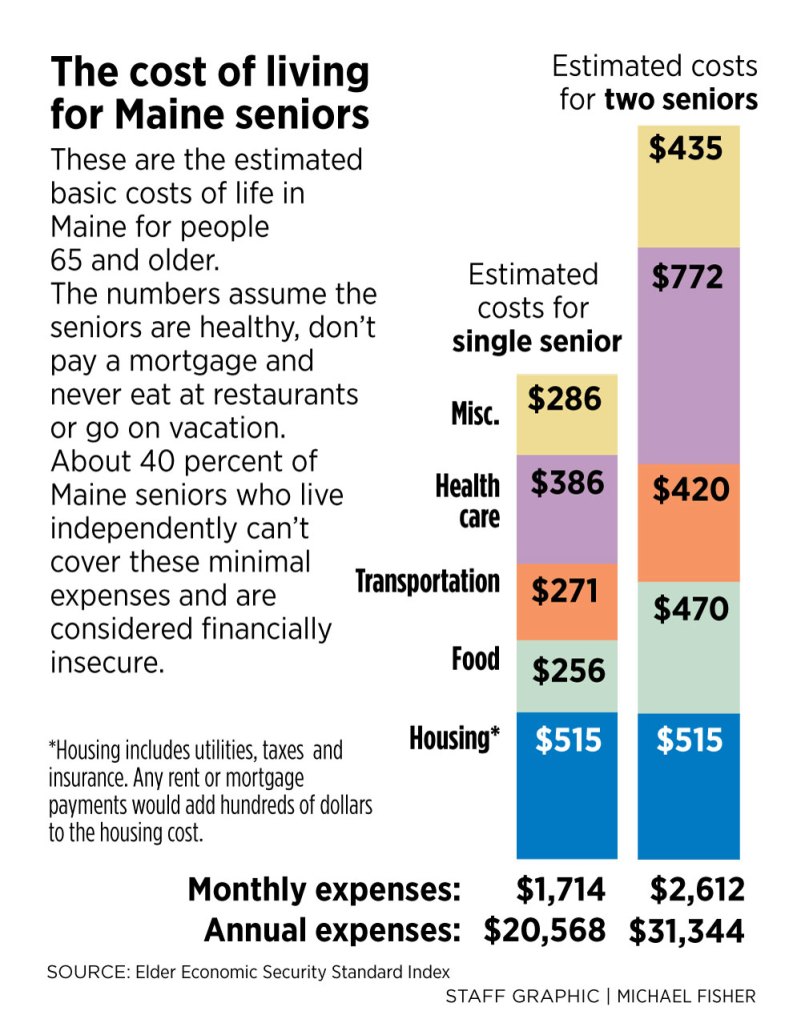

Rena Heath’s $1,500 monthly pension adds up to $18,000 per year. That’s almost $6,000 above the federal poverty level, which is $12,140 for a single person, but it falls nearly $5,000 short of the $22,848 annual income that the Elder Index says she needs to cover basic expenses, without any extras. Like the coffee she sips while reading a book in a sunny window at Slates bakery in downtown Hallowell. She reads a lot. She hasn’t had a TV for a while.

Single with no children, Heath pays nearly $500 to rent her apartment in subsidized senior housing. That leaves about $1,000 for other monthly expenses, including food, clothing, prescription co-pays, any unexpected bills and occasional taxi rides because she no longer drives and can’t always count on friends to get where she needs to go.

Heath has a little savings, about $5,000 she put away near the end of her career, but she knows that won’t last long if she has a major emergency or needs some form of long-term care. Last year, Heath’s monthly pension increased by $39, but her rent went up $18 and other expenses followed suit, she said. Two years ago, a change in health coverage for state retirees added $600 in deductible medical costs to her annual expenses, she said.

“I realize to people who have a lot of money, that’s not much,” Heath said. “But when you don’t have much, that’s a lot.”

Seniors who fall below the Elder Index might own their homes, though many don’t, and they might be active in their communities, like Heath, who regularly attends senior luncheons and State House hearings on elder issues. But often they can’t afford any extras and must make tough choices between paying for prescriptions, buying personal care items, subscribing to basic cable television or putting gas in the car.

In Maine, single older renters like Heath need a yearly income of $22,848 to cover the basics, while two-senior rental households need $33,624, according to the Elder Index. The national average is $23,364 for single seniors and $33,876 for two-senior households. Federal poverty income level is $12,140 for a single person and $16,460 for a two-person household.

For older Mainers who own mortgage-free homes, the Elder Index is $20,064 for singles and $30,576 for two-senior households. For older Mainers with a mortgage, the Elder Index is $30,972 for singles and $41,484 for two-senior households. Published in September 2016, the Elder Index is expected to be updated this year using 2018 data reflecting 5 percent cost increases, said Mutchler, the demographics expert.

The Elder Index doesn’t allow for vacations, restaurant meals, large purchases, gifts or entertainment of any kind. It also doesn’t allow for increasing savings. That’s a significant challenge facing many seniors across the United States and in Maine, where the typical working household has just $3,000 in retirement savings and the average Social Security income is $16,000, according to elder advocates.

“Thanks to Social Security, fewer seniors are living in poverty,” said Lori Parham, state director of AARP Maine. “But costs are rising and people are living longer and many retirees have very little savings. We’re expecting to see an increase in senior poverty because Social Security benefits aren’t going to keep up.”

NO RETIREMENT SAVINGS

Philip Christy started working full time when he dropped out of Portland High School as a junior and took a job as a bundle boy at Shaw’s supermarket. He went on to work as a longshoreman, truck driver, grocery manager and baker. He even put in several years with the Maine Army National Guard.

“I always worked,” said Christy, 86, a widower who lives in Scarborough. “Matter of fact, I worked two jobs for a while, with four kids and trying to make a house payment.”

Disabled by a serious heart attack at age 59, Christy gets by today on his monthly $1,460 Social Security check, which is quickly consumed by a mortgage payment, utilities, taxes, repairs to his modest Cape and his 2005 automobile, and other expenses. To cover those basic needs, the Elder Index shows he needs a monthly income of $2,372, or $30,972 per year.

To stretch his annual $17,520 Social Security benefit, Christy said he visits the town’s food pantry for staples such as canned goods, cereal, eggs and cheese. He’s a regular at local senior lunches, where payment is optional, and he goes on occasional day trips for seniors if they don’t cost too much. He enjoys discount coffee at McDonald’s every morning with friends and he gets free and reduced phone services through programs for seniors. Medicare covers his growing medical needs.

But he has no retirement savings. When he was working, his paychecks usually weren’t large enough to put much away.

“And every place I worked, I never got any retirement benefits,” Christy said.

PENDING FEDERAL BILLS

Not much has changed since Christy was driving trucks or baking bread. Nearly half of Maine’s private sector employees – about 254,000 Mainers – don’t have access to a retirement savings plan at work, according to the National Institute on Retirement Security. And access is a key factor.

People earning $30,000 to $50,000 per year are 16 times more likely to save for retirement if a workplace plan is available, the Employee Benefit Research Institute found. Moreover, Maine could save as much as $23 million on public assistance programs over the next 15 years if lower-income workers could save enough to increase retirement income by just $1,000 per year, according to the AARP Public Policy Institute.

Sen. Collins introduced two federal bills this year that would help people avoid Christy’s situation. One is the Retirement Security Act of 2019, which would make it easier and more affordable for smaller businesses to join so-called Multiple Employer Plans. It also would allow employees to receive an employer match for contributions up to 10 percent of their salary and would give businesses with fewer than 100 employees a tax credit to offset their increased contributions.

The second bill would upgrade SIMPLE retirement plans, which were established in 1996 to be less costly and easier to manage than 401(k) plans for businesses with 100 or fewer employees. The bill would increase annual contribution limits for employees, allowing them to save more on a tax-deferred basis.

Collins said she’s also working to increase funding for programs that help keep seniors in their homes, including safety and technology upgrades, and she noted the need to increase Medicaid funding for home care and long-term care.

But she acknowledged that none of these efforts will help boost retirement savings for current seniors or increase wages for low-income workers who otherwise still won’t be able to save much for retirement. She also acknowledged the growing need for accessible senior housing and the lack of transportation for seniors in rural Maine.

“It’s a real problem,” Collins said. “The demographics are overwhelming now and the needs are only going to skyrocket.”

LONG-TERM CARE NEED

With no savings and limited income, Philip Christy knows his options and relative independence would soon evaporate if he became further disabled by illness and required some form of long-term care.

“We did my funeral arrangements, me and my daughter, but we haven’t thought about long-term care,” Christy said.

Moving in with one of his kids isn’t an option. “I wouldn’t want to burden them,” he said. “I’d go into a home.”

But finding long-term care is becoming more challenging in Maine, where seven nursing homes closed in the last 15 months, largely because long-term care facilities are increasingly dependent on Medicaid funding that’s already falling short.

Today, there are 93 nursing facilities statewide, down from 132 in 1995, said Richard Erb, head of the Maine Health Care Association, which also represents 127 assisted-living facilities. The latest nursing home closures were Mountain Heights in Patten, Sunrise in Jonesport, Ledgeview in West Paris, Freeport Nursing in Freeport, Bridgton Health in Bridgton, Fryeburg Health in Fryeburg and Sonogee in Bar Harbor.

“All of the homes that closed were relatively small and relied heavily on the MaineCare program for their livelihood,” Erb said, noting that two-thirds of nursing home residents in Maine are covered by Medicaid.

And while the Maine Legislature recently increased Medicaid reimbursement rates to nursing homes, they continue to experience dramatic increases in labor costs, Erb said. As a result, Medicaid reimbursements to Maine nursing homes fell short by $33.3 million in 2017 – $7.5 million more than the Medicaid shortfall in 2016.

Erb worries that Maine won’t have enough nursing homes as its senior population blossoms in the coming years. Maine currently has 24 nursing home beds for every 1,000 people age 65 and older, compared with 36 beds per 1,000 seniors nationwide, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

And while long-term care insurance can help seniors pay for assisted-living, nursing home and home care, less than 10 percent of older Mainers have purchased the coverage, Erb said.

The biggest challenge facing Maine nursing homes and assisted-living facilities is the rising minimum wage amid a nationwide workforce shortage, Erb said. The combination is making it difficult to hire and retain certified nursing assistants and personal support specialists, who make up a significant portion of long-term care workers. Several state proposals this spring would again increase and streamline Medicaid funding for long-term care.

“(Increasing wages) is a good thing,” Erb said. “We just have to figure out how to pay for it. Our facilities are competing with other segments of the labor market and there are many easier ways to make a living than working in long-term care.”

CHALLENGES TO COME

Paul Armstrong embodies the breadth of challenges facing older Mainers, and he’s not yet 65.

Armstrong was working construction in 2004 when he fell 32 feet and landed on his heels, he said. Crippling compression fractures left him with excruciating chronic pain, arthritis, degenerative disc disease and other serious health problems.

Now 59, the former restaurant owner can walk only short distances and stand for short periods. Armstrong receives a $1,250 Social Security disability payment each month, or $15,000 per year. Based on the Elder Index, he needs an annual income of $20,568 to cover basic expenses.

Instead, his health care is mostly covered by Medicare and MaineCare. He also receives $193 per month in food stamps and $900 a year in fuel assistance, which buys a tank and a half of propane to run his refrigerator, space heaters and other appliances in his off-the-grid home.

Increasingly, however, the hillside house he built in rural Palermo in the early 1990s – a wood-, wind- and solar-powered refuge with views across the Kennebec River Valley – is becoming a burden to maintain and a source of unrelenting worry.

His fear is magnified at the end of each month, when he finds himself broke after paying regular bills such as property taxes, insurance, car repairs and credit card debt that mounted after his divorce.

He hires help to stack wood and do other chores when he can afford it, but the idea of leaving the home he loves and moving into an apartment depresses him. He knows there are long waiting lists for subsidized housing that’s accessible to disabled seniors, and that ongoing efforts to promote senior housing development wouldn’t benefit him for a while.

“I’m scared about the future,” Armstrong confessed. “I’ve got nothing put away and I’ve got no one to take care of me. I love this place, but it’s getting to be too much for me now. I’ve been considering moving for a while, but I don’t know where I would go.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story