If you’ve never stood before a judge inside courtrooms in Auburn, Paris and Rumford, good for you, but too bad for your art-loving self.

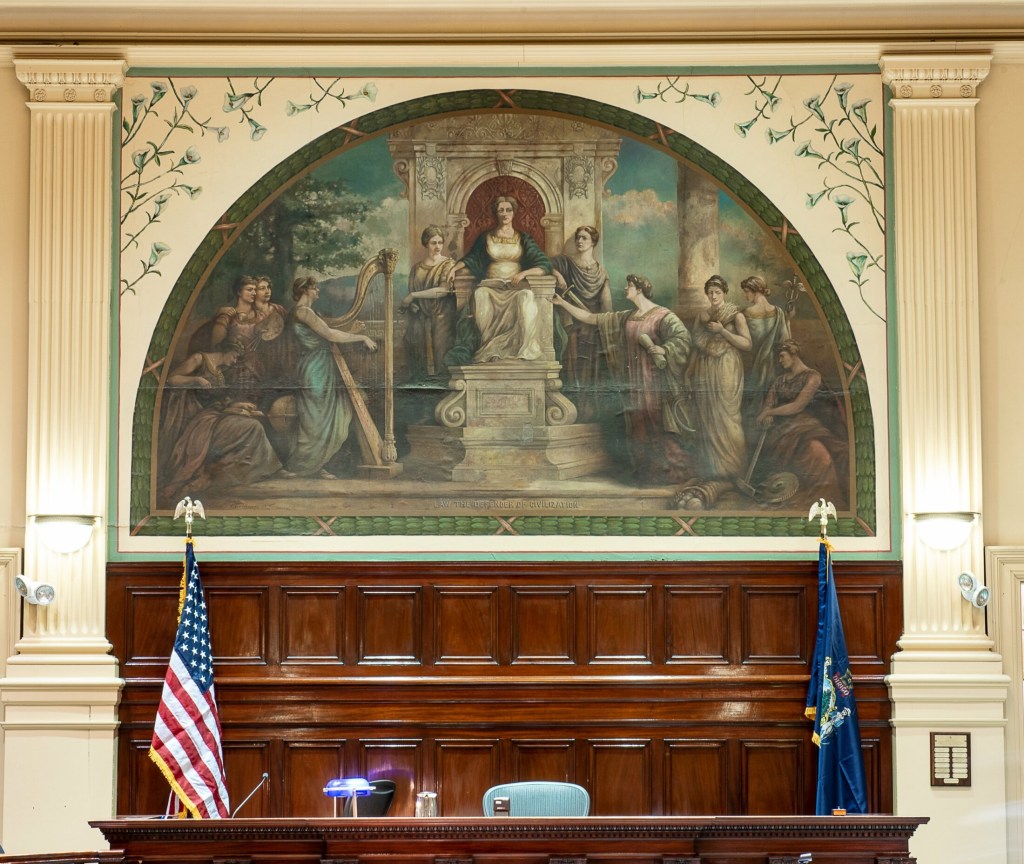

A mural painted by Harry Cochrane, a Monmouth artist who died in 1946, hangs behind the judge’s bench at Androscoggin County Superior Court in Auburn. The mural is bookended by portraits of former superior court justices. Sun Journal photo by Russ Dillingham

It’s where to find some of the most striking work of “the Michelangelo of Maine,” Monmouth native Harry Cochrane.

Before he died in 1946 at age 86, Cochrane, a renowned muralist, architect and composer, had painted all over the country in his signature fresco style.

At different points in his prolific career, Cochrane left his mark on the three Maine courts, each with a giant, 15-by-10-foot mural hanging behind the judge’s bench.

Inside Rumford District Court, “Birth of Law,” showing Moses in a red robe standing against a backdrop of mountains, staring worriedly into the sky while clutching tablets with the Ten Commandments written on them. In the distance, a thunderbolt is erupting from a dark gray cloud.

In the Androscoggin County courthouse, “Law, the Defender of Civilization,” featuring a woman personifying the concept of “law,” sitting on a throne and surrounded by 10 women. The woman on the throne wears a beige dress with a green shawl draped around her shoulder. She is holding a scale in her right hand and an open book is resting in her lap. A woman to her left is playing a harp, while another to her right is holding a sword and looks to the side.

A similar mural – “The Code of Justinian” – is set up behind the judge’s bench in Oxford County courthouse. The mural, named after a written collection of Roman laws from the sixth century, portrays Justinian I, an Eastern Roman emperor, ordering jurists to compile all of the existing Roman law into one body of work.

Cochrane was known informally by locals as “the Maine Leonardo” or the “Michelangelo of Maine.” Historian Marius B. Peladeau wrote in “A Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Maine” that the exact number of buildings Cochrane decorated between 1887 and his death “will never be known, since no complete record of his output survives and his geographic coverage was so broad.”

“At one time, it would probably have been easier to name towns in Maine without Cochrane commissions than to list those with his work,” Peladeau added.

JACK-OF-ALL-TRADES

Little is known about the mural entitled “The Code of Justinian” that Monmouth artist Harry Cochrane painted for the Oxford County Superior Court. Cochrane was responsible for painting several murals for Maine courtrooms, including in Auburn and Paris, and was commissioned by Paris to decorate the Paris courtroom and design the courthouse furniture. Sun Journal photo by Russ Dillingham

Cochrane was born in April 1860 to James Cochrane of Limington and Ellen Berry of Belfast.

His mother died when he was young, and his father was an architect who served for years as supervising architect of government buildings in Washington D.C., which meant Cochrane was raised by his grandparents in Monmouth.

During that time, he attended Monmouth Academy, where he began drawing at a young age.

According to “Maine Biographies,” written by Harrie B. Coe in 1928, Cochrane became interested in mural painting after a fresco artist visited Monmouth to decorate and paint a church.

When he was 18 years old, he began portrait painting. Nine years later, when he was just 27 years old, he decorated his first church.

Throughout his 20s, Cochrane was a tireless worker. According to Peladeau, Cochrane gave art lessons in Brunswick at the age of 21, and five years later, partnered with a Waterville photographer to create photographic portraits.

During the same time period, he designed and superintended the architecture and decoration of a variety of fairs in Boston and did decorative work for a department store in New York.

Over the next several decades, Cochrane earned a reputation as a jack-of-all-trades. He composed and performed music, designed buildings, and was commissioned by dozens of towns in Maine and by other New England states to paint murals and design and decorate buildings.

Cochrane became well-known for painting ecclesiastical art, or art related to the church. He painted in the fresco style, a common method by mural decorators of painting on fresh or wet plaster.

In 1900, when he was 40, Cochrane was commissioned by Dr. Charles M. Cumston of Monmouth to design a new town hall for the community. Cochrane had never designed a building before, but people were familiar with his painting skills and his father’s reputation as an experienced architect and took a chance on him. The building became Cumston Hall, still used by the community today.

From 1900 to 1946, Cochrane was commissioned to decorate or design more than 400 different buildings throughout New England.

State officials commissioned Cochrane to design the State of Maine Centennial coin in 1920 for the U.S. Mint.

He also gained some notoriety for the 15 murals he painted for the Lewiston Kora Temple between 1922 and 1927.

THE COURTHOUSE MURALS

The mural hanging behind the judge’s bench in Rumford District Court — entitled “Birth of Law,” and painted by Monmouth artist Harry Cochrane — hasn’t moved in nearly 100 years. Cochrane, who died in 1946, also painted murals for the Oxford and Androscoggin counties’ superior courts. Sun Journal photo by Russ Dillingham

Despite the large quantity of Cochrane’s murals scattered throughout New England, little is known about the murals he painted in the three local courthouses.

According to the Lewiston Daily Sun archives, Cochrane was commissioned by the Androscoggin County Superior Court to redecorate the interior of the courtroom in July 1940.

A Lewiston Daily Sun article from Oct. 2, 1985, stated that Cochrane painted the Rumford courthouse mural in 1923, six years after the municipal building housing the courtroom was built.

That mural has sat behind the judge’s bench for nearly 100 years. In 1985, after a roof leak caused water damage, the Rumford Historic Preservation Commission hired Lee Snow, a painting conservator from Falmouth, to clean it and restore it.

The mural at the Oxford County Superior Court is the least documented of the three.

The courthouse in Paris was constructed in 1895 by Lewiston architect G.M. Coombs, but there is nothing in the Sun Journal archives dating back to that year about Cochrane painting a mural for the courthouse.

Randall Bennett, executive director of the Bethel Historical Society, said that he suspects Cochrane painted the mural shortly after the courthouse was built, but he was unable to find anything confirming his suspicion.

The only documentation of the mural at the courthouse in Paris is in the bibliography section of a thesis paper written in 1950 for Bates College by the late Arthur Griffiths of Monmouth.

In the bibliography, Griffiths wrote that Cochrane was responsible for decorating a mural painting and furniture for the Oxford County Superior Courthouse. He noted in his thesis paper that he relied on Cochrane’s personal records as his source of information, which he had in his possession at the time.

Peladeau said in a March 2 interview with the Sun Journal that Cochrane’s art studio burned down late in his life, resulting in a loss of records documenting his commissions.

“It’s possible there was a paper somewhere or a bill from Oxford County to paint the mural, but it may have been lost in the fire,” Peladeau said.

BIG-CITY ART IN A SMALL TOWN

Cochrane’s murals have continued to enamor Mainers long after his death. Bennett said that Cochrane was interesting and “far from an amateur.”

“He dabbled in all kinds of things, whether it was architecture, art, painting portraits, painting landscapes, writing,” Bennett said. “He was a prominent enough artist that he was commissioned to do mural paintings in important public spaces.”

Peladeau said that he was drawn to writing a biographical essay on Cochrane after becoming familiar with his murals while serving as executive director of the Theater at Monmouth, located inside Cumston Hall.

“(Cochrane was a) talent that you would expect to find in a big city, not in a small town in Maine like Monmouth,” he said, adding that he was pleased to hear that Rumford had spent the time and money to restore the painting in the Rumford District Court.

“It’s nice to see that a lot of these buildings and places are willing to keep these murals up there and keep them in good shape,” Peladeau said. “I feel like the new generation doesn’t care as much about these types of mural paintings. It’s nice to see them still getting some attention.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story